José Martí and His Entry into Prison

In the face of outrage sparked by Spain’s treatment of Cubans during the uprising of October 10 and the Grito de Yara, the resilience and alignment of personal and national interests among Cubans in the second half of the 19th century gave rise to two opposing currents shaping the destiny of the largest archipelago in the Antilles. Fueled by a deep love for his homeland, José Julián Martí Pérez stood firmly with those who dreamed of an independent Cuba.

On October 4, 1869, members of the Volunteer Corps, returning along Industria Street, stopped at the home of Fermín Valdés Domínguez after hearing the laughter and chatter of the young men gathered there. They detained everyone present. A search of the house uncovered a letter addressed to Carlos de Castro, a student enrolled in the Volunteer Corps, inviting him to respond amid the tense political climate gripping Cuba. Signed by Martí among others, the letter posed a pointed question: “Comrade, have you ever dreamed of the glory of apostates? Do you know how apostasy was punished in ancient times? We trust that a disciple of Mr. Rafael María de Mendive will not leave this letter unanswered.”

Influenced by his mentor Rafael María de Mendive and the insurrection launched by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, Martí—a young man surrounded by like-minded patriots—placed his commitment to Cuba above the hollow promises of those who falsely boasted of their service. On October 21, Martí was arrested too. During the trial, both he and Fermín Valdés Domínguez tried to shoulder the bulk of the blame for drafting the letter. “But Martí’s passionate arguments convinced the court of his greater guilt, leading to the harshest sentence,” notes journalist Víctor Pérez-Galdós Ortiz.

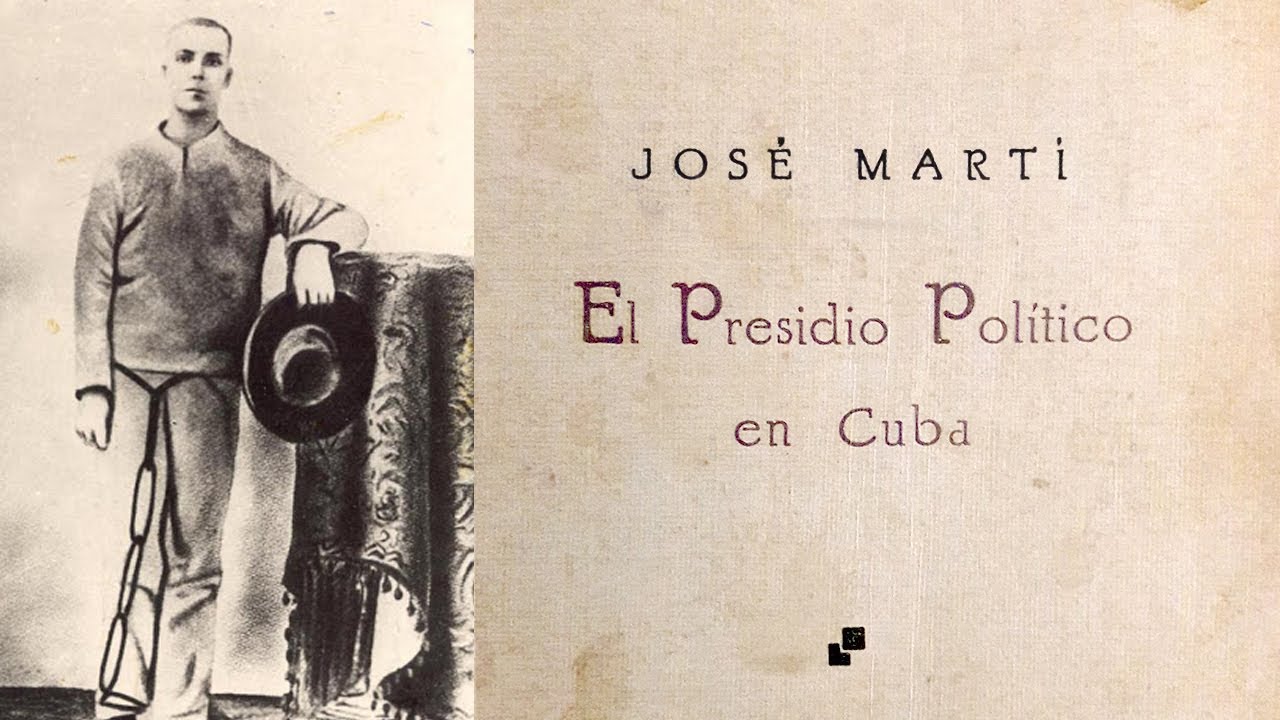

From his prison experience emerged the Presidio Político en Cuba, written in 1871 after his exile to Spain—a move facilitated by his father’s efforts to lighten the punishment of the seventeen-year-old. This work not only served as a bold denunciation of the colonial system in Cuba but also revealed the humility, resolve, and humanity of its author, who would later shape the independence struggle and provide the moral foundation for what became known as the Necessary War.

Journalist Rosa María Medina Borges observes: “Martí, despite his youth, displays a wealth of cultural and ethical depth in this piece. It reveals the strength and greatness of the man and writer he would soon become. From this text, we see an ideological maturing of his vision of the homeland, tied to political, human, and moral values forged through a commitment free of hatred or resentment.”

Researcher Rosa María García Vargas adds: “Even at such a young age, Martí was fully aware of his duty to his country and his peers, whom he refused to implicate. Yet the harsh reality of prison—the horrific conditions, the abuses, and the indignities inflicted on inmates—weighed heavily on his heart.” She argues that such trauma would have left a lifelong mark on anyone else. For Martí, however, it fueled a determination to rise above the pain, driven by the urgent need for Cuba’s independence.

“Amid the terrible suffering of prison,” she continues, “he countered despair with a remarkable optimism, fighting with unwavering faith in ultimate victory. That’s why he wrote in this testament: ‘The notion of good floats above all and never sinks.’”

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez

Photo: YouTube