Rita Longa and the Complement to the Avant-Garde

The avant-garde movement found a fertile and unburdened pathway in the artistic trajectory of Rita Longa. Throughout her career, the Cuban sculptor explored various themes associated with this movement—initially through small-scale works and later through large-scale environmental pieces. In doing so, Longa emerged not only as a key reference point but also as an indispensable figure in the history of Cuban sculpture.

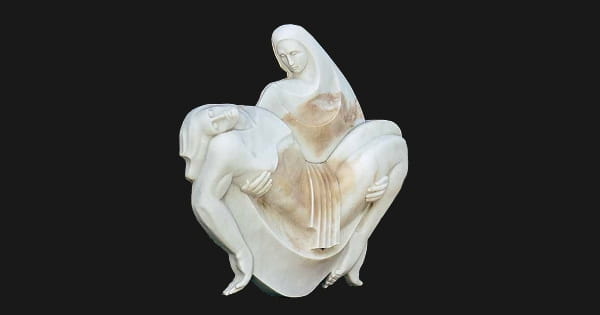

The female figure is a recurring motif in her work, often imbued with a religious dimension. Many scholars and critics believe this element broke with the artistic conventions of her time and contributed to her lasting legacy. Her prolific output further reinforced her influence, with works that enrich the Cuban landscape across the island—ranging from environmental sculptures to commemorative monuments.

The richness of her stylistic repertoire and the expressiveness of her sculptural work were also shaped by collaborations with other professionals, which fostered creative exchange and fueled her artistic growth. A clear testament to this is her masterful ability to integrate her sculptures into their surroundings. Rather than disrupting the environment, her works harmonize with it, enhancing the surrounding architecture.

As one researcher observed: “The significance of her work lies in how it became part of the people’s everyday life, positioning her at the pinnacle of Cuban sculpture across all eras.” When Rita Longa passed away on May 29, 2000, the nation bid farewell not only to a prolific and accomplished woman but also to one of the greatest sculptors in Cuban art history.

Recipient of the National Visual Arts Award, Longa was a founding member of the UNEAC (National Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba), and directed and taught at the Guamá Workshop School in the Zapata Swamp, where she later helped establish a namesake museum in that community.

In her book Las manos de Rita, researcher María de los Ángeles Pereira notes that, early in her career, the artist drew from rich textures that elevated the expressive autonomy of her materials. “(…) Beginning in the early 1930s, her bold career reflects the Cuban creators’ early drive for change and renewal, while also illustrating the swift and monumental evolution of our sculptural avant-garde.”

From works such as Forma, espacio y luz near the National Museum of Fine Arts, La muerte del cisne outside the National Theater, or the Virgen del Camino sculpture in the municipality of San Miguel del Padrón, the visible vitality of Longa’s creations asserts a harmonious and undeniable presence—integrated into the landscape not as foreign objects, but as enriching and essential elements.

To quote Professor María de los Ángeles once more: “Her ideas were, time and again, concepts transmuted into forms never confined by the limits of a single expressive tendency. Rita moved effortlessly between a practice indebted to—but never subservient to—the figurative tradition, and a resolutely abstract language, particularly where she sensed our sculptural scene most in need of the metaphorical breath of abstraction.”

That legacy, present throughout Cuba, demands a renewed look at her life and work—a woman untouched by the passage of time and one of Cuba’s most prominent artists. Reflecting on the endurance of her figure and her creations, she once stated in an interview: “People know my work because they’ve been seeing it for over 60 years. That’s the only reason for my popularity. It’s time, repetition—that’s what establishes an artist’s work. Whether their name is remembered or not doesn’t matter. What remains is the work.”

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez

Photo: Photos of Havana