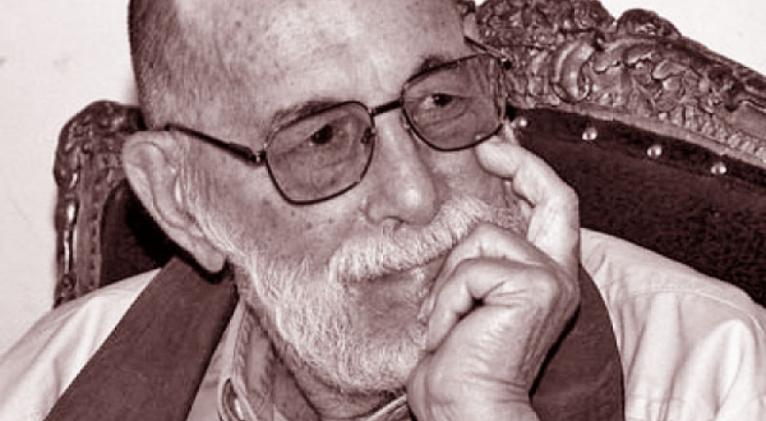

Emilio Roig de Leuchsenring: Cuba’s Historical Conscience

Havana, with its colonial squares and streets steeped in history, found in Emilio Roig de Leuchsenring not only its first official historian but also a passionate defender whose life became deeply intertwined with Cuba’s national identity.

Born on August 23, 1889, in the nation’s capital during the final days of Spanish colonial rule, Roig grew up amid the echoes of independence. As a child, he visited mambí rebel camps with his father, a supporter of the revolutionary cause—an experience that left an indelible mark, symbolized by the small Cuban flag pinned to his boyhood hat.

This early immersion in the spirit of liberty would shape his path as an intellectual committed to safeguarding Cuba’s sovereignty against any form of foreign domination.

Educated at Havana’s prestigious Colegio de Belén, Roig earned his doctorate in Civil and Notarial Law from the University of Havana in 1917. Yet his true vocation revolved around the written word and historical research.

His career began in 1905, when the Diario de la Marina published his travel essay Impresiones de viaje. It marked the start of a prolific literary journey spanning genres from costumbrista sketches and political satire to rigorously documented historical essays.

Roig’s sharp, agile pen gained recognition in 1912, when he won first prize in El Fígaro magazine’s humorous article contest with ¿Se puede vivir en La Habana sin un centavo? The piece revealed his gift for blending social observation with biting critique—a hallmark of his work, which combined intellectual depth with accessibility for a broad audience.

In the 1920s, Roig emerged as a central figure in revolutionary intellectual circles, though he remained, in the words of several Cuban sources, an “essential revolutionary without party affiliation.” His law office became a meeting place for the Grupo Minorista, where he collaborated with Rubén Martínez Villena, Juan Marinello, and Alejo Carpentier, forging creative alliances between art and political commitment.

He took part in the Protesta de los Trece in 1923, a civic act of defiance against the corruption of President Alfredo Zayas’s government, and joined the Falange de Acción Cubana. He was also a co-founder of the Anti-Imperialist League alongside Carlos Baliño and Julio Antonio Mella, cementing his opposition to foreign interference—a central theme in his historical work. Jorge Mañach would later describe him as the Grupo Minorista’s natural leader, the “enfant terrible” whose incisive words and sharp irony unsettled the complacency of the so-called pseudorepublic.

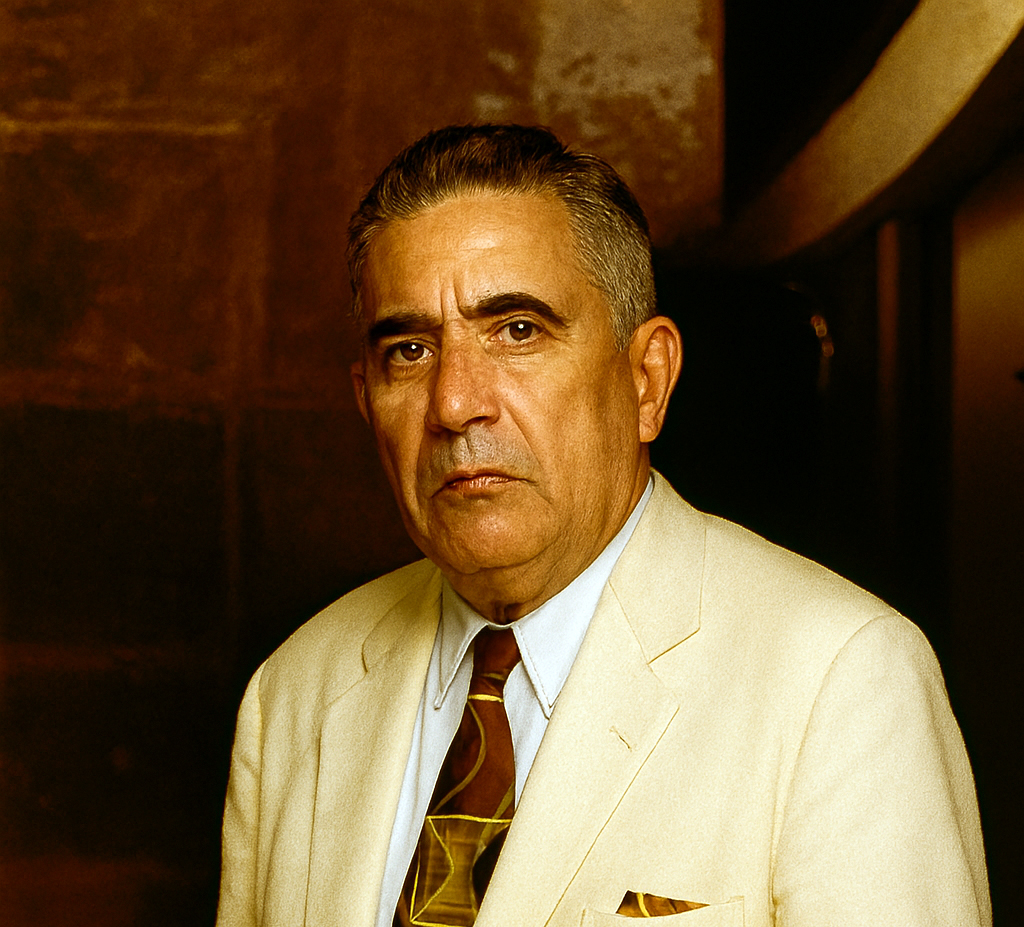

July 1, 1935, marked a turning point in Roig’s life: he was appointed Havana’s first official historian. In 1938, he spearheaded the creation of the Office of the Historian, which became the nerve center of heritage preservation and historical research in Cuba.

From this platform, Emilio Roig launched lasting cultural initiatives, such as the free distribution of Cuadernos de Historia Habanera to schools, the founding of the Museum of the City in 1941, and the creation of the Commission of Historical Monuments. His vision extended beyond colonial history to encompass the full historical spectrum of Havana, including popular traditions and underrepresented cultural expressions.

In 1942, he organized the first National History Congress, was elected president of the Society of Freethinkers, and promoted cultural exchange with Mexico, the Dominican Republic, and the Soviet Union, which is clear evidence of his internationalist approach to knowledge.

Roig’s writings serve as an arsenal against historical amnesia and distortion. His landmark work, Historia de la Enmienda Platt: Una interpretación de la realidad cubana (1935), meticulously dismantled the mechanisms of U.S. neocolonial control, linking the past to the pressing challenges of the Cuban republic. Later titles, such as Cuba no debe su independencia a los Estados Unidos (1950) and Hostilidad permanente de los Estados Unidos contra la independencia de Cuba (1960), continued this line of thought, combating what he termed the “fatal inferiority complex” instilled in Cubans by the false notion that their freedom was owed to U.S. intervention.

His anti-imperialism was grounded in documents and eyewitness accounts. For example, he demonstrated that the Spanish-Cuban-American War was essentially won by the Cuban Liberation Army under the command of Calixto García.

Roig also rescued and reinterpreted foundational figures through biographies like Máximo Gómez, el libertador de Cuba y el primer ciudadano de la República (1959) and provocative works such as La iglesia católica y la independencia de Cuba (1958), maintaining the polemical edge that defined his intellectual persona.

José Martí occupied a central place in Roig’s patriotic vision. From his 1938 induction into the Academy of History with Martí en España to later works like La revolución de Martí, 24 de febrero de 1895 (1941) and El pensamiento político de Martí (1960), Roig devoted himself to unveiling and disseminating Martí’s legacy, especially its anti-imperialist dimension.

In a culturally significant gesture, he reissued La Edad de Oro in 1932, preceded by his study Martí y los niños, introducing this seminal work to new generations at a time when the state scarcely promoted national culture.

Equally valuable was his revival of Julio Antonio Mella’s essay Glosas al pensamiento de José Martí, which he published as a pamphlet in the late 1930s, reclaiming the first Marxist analysis of Martí’s thought at a time when Mella’s name was still silenced under Gerardo Machado’s tyranny.

For Roig, this scholarship on Martí was not mere erudition but a tool for shaping national consciousness. “To be Cuban is to be anti-imperialist,” he declared, distilling into one sentence an entire philosophy of cultural resistance.

After the triumph of the Cuban Revolution in 1959, Roig’s decades of work were recognized. In a 1960 speech, Fidel Castro called him a “true master of our history” who chronicled “our nation’s efforts for more than a century to be a free country.” His protégé and eventual successor as Havana’s historian, Dr. Eusebio Leal, recalled learning from Roig: “He was an ally of perfection and detail. When he left the office, everything was done.”

Leal later remarked, “Without Emilio Roig, there would be no Eusebio Leal,” remembering him as a sharp-eyed man, always immaculately dressed in white, whose powerful voice was gradually silenced by a vocal cord illness in his later years—a cruel irony for someone whose most potent tool was the spoken word. Roig died on August 8, 1964, just days shy of his 75th birthday, leaving behind a body of work that transcends time.

Today, his legacy lives on not only in institutions such as the Emilio Roig Chair at the Cuban Institute of History and the colloquium that bears his name, but also in the very historical consciousness of the nation. His greatest contribution was showing that history is not a museum of relics but a battlefield where identity is forged—and that rigorously naming the past is the first act of sovereignty. As Leal aptly put it, “We have contributed a grain of sand to raise the pedestal of his monument,” a pedestal that stands in every serious study of Havana, in every street restored to its historic name, and in every Cuban who understands that independence was not granted but won.

Sixty years after his death, the city he loved continues to engage in dialogue with his work—a testament to the truth that historians, when they are true makers of memory, never entirely die.

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez