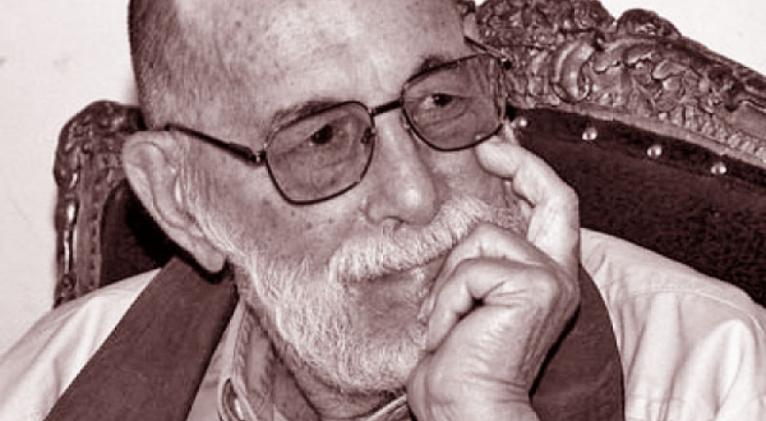

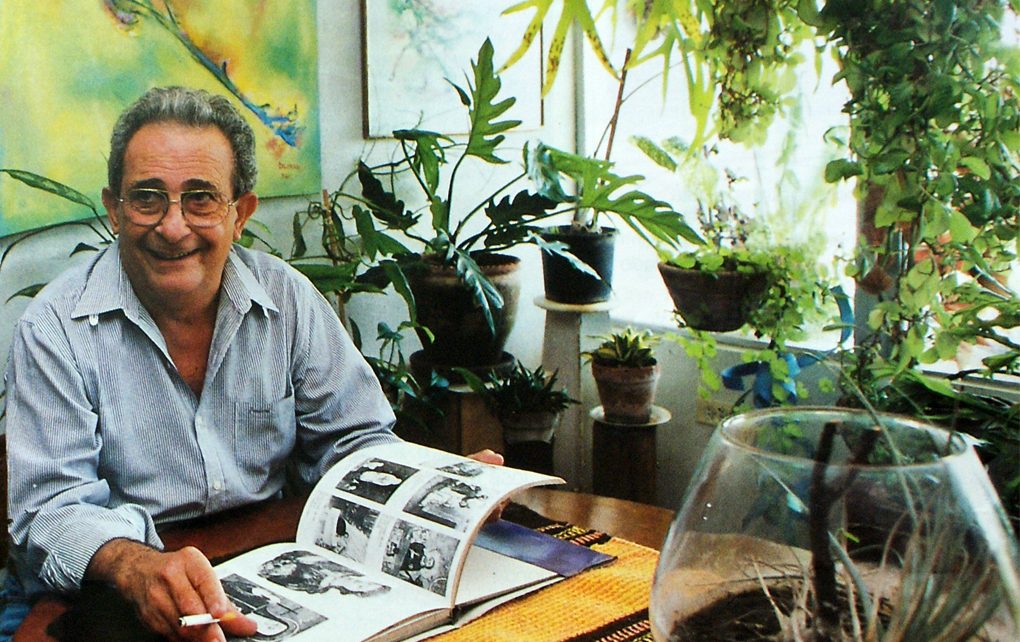

José Delarra: The Innocence of Oblivion

When José Delarra passed away on August 26, 2003, many felt the presence of a giant quietly fading from the world. Humble and free of rancor, he was untouched by the «-isms» of art and the pomp that often surrounds it. He generously gave away much of his vast body of work. “Delarra did not paint in the style of anyone nor did he enter into binding contracts or arrangements with gallerists or collectors whose interests were more shaped by commerce than by pure art,” noted journalist and art critic Jorge Rivas.

His creative reach extended beyond sculpture; painting, ceramics, and drawing also found new avenues of expression in his hands. He poured his spirit into a vast canvas, leaving behind enduring traces of his artistic personality without diminishing the breadth of his oeuvre.

As the sculptor of Che, the National Hero of Labor, and a chronicler of the Revolution, Delarra was also a member and deputy of the International Association of Plastic Artists. Among his most notable works are the Ernesto Che Guevara Complex in Santa Clara, public squares in Bayamo and Holguín, and monuments dedicated to Friedrich Engels, Máximo Gómez, the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the Rosenbergs. His works also commemorate the history of Mexico and José Martí in Cancún, as well as internationalism in Luanda.

Delarra was a teacher and director of the San Alejandro Academy. Passionate about making art accessible to the public, he was laid to rest with honors in the Pantheon of the Armed Forces. However, recognition of his impact on the artistic landscape still shows notable omissions. “Perhaps, in his steadfast enthusiasm for pursuing his aesthetic concerns freely and without prejudice, lies another part of the moral price he had to pay in life: the near-total neglect of his work by the system of institutional galleries and promoters of contemporary art on the island,” Rivas observes. He reflects on the artist’s legacy, stating, “An unjust paradox. Delarra—the indisputable artist, the affable Cuban wholly committed to the cause of the Cuban Revolution—has been overlooked in most books, essays, lectures, and studies on contemporary Cuban art. In the face of such inconceivable circumstances, the prolific ceramist sustained his creativity with the utmost ethical dignity. He considered himself ‘the wrong kind of man, for I am a politician who turned to art.’ Just as neglected was the decision—repeatedly postponed by those in power—to grant him the much-deserved National Prize for Visual Arts, an honor that should have been his in life. With characteristic modesty, he told me a few months before his death, ‘Perhaps I still do not deserve it.’”

For some, Delarra’s career is summed up merely by calling him a chronicler of the Cuban Revolution. While this title is significant, it does not fully encompass the mastery that defined his entire body of work. His sculptures exhibit near-hyperrealistic precision—an enviable quality in itself. Not even the National Museum of Fine Arts holds a single piece of his, whether it be a painting, drawing, sculpture, or ceramic.

According to Rivas, José Delarra’s pictorial works reflect a vigorous study of light and texture, applying layering techniques and styles that touch on abstraction without completely embracing it. His art rests in the gesture itself, its movement and orchestration, creating a unity where observation, understanding, and enjoyment merge.

Until his final days, Delarra defied labels. To reduce his production to socialist realism is to misunderstand the depth of his work—a commitment of an unprejudiced artist who bore the weight of dogma yet overcame obstacles with creativity, talent, and an indelible force.

As Rivas aptly concludes: “By rejecting the classical line as the ultimate solution—whether in his sculptures or in his broader iconographies—he confirmed that his art could transcend through the interplay of figuration, abstraction, and surrealism. He demonstrated that art—as a fantasy of man—is nothing less than the very soul of reality, born from harmony or discord between humanity and its time, its environment, and the world it inhabits.”

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez

Photo: Cubaperiodista