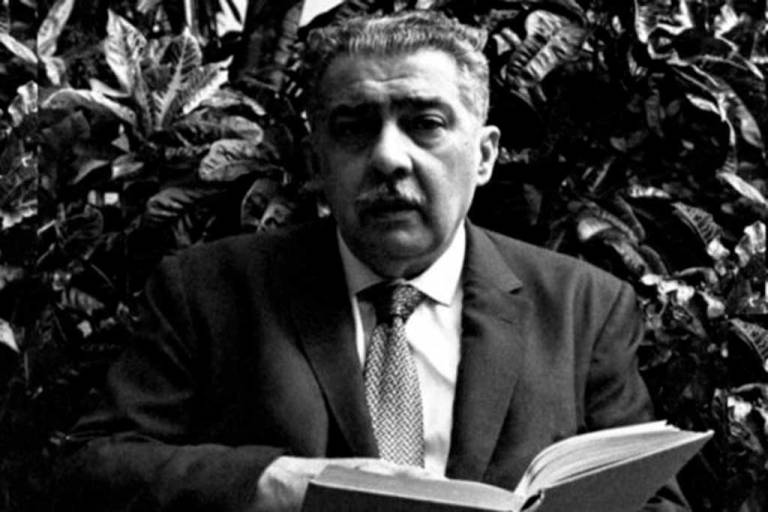

José Lezama Lima: Architect of a Baroque Universe

Within the Cuban and Latin American literary landscape, the figure of José Lezama Lima (1910–1976) stands as a beacon of dazzling complexity and radical originality. Far more than a writer, Lezama was an aesthetic thinker, a creator of poetic systems, and a cultural catalyst whose work ranks among the most ambitious linguistic and metaphysical adventures of the twentieth century. Through a baroque style entirely his own—reimagined and reinvented—he constructed a literary cosmos in which image, metaphor, and erudition converge to reveal, in his own words, “the reality of the invisible world.”

Lezama’s biography is marked by a foundational loss that profoundly shaped his sensibility. His father, Colonel José María Lezama, died when the future poet was only nine years old. This event, which he would later describe as “the pulse of absence,” instilled within his family—especially his mother—the conviction that his destiny was to tell the story of the family. That narrative mission, woven from memory and myth, would find its fullest expression decades later in his masterpiece, Paradiso.

Lezama was formed as an omnivorous reader and a committed intellectual. He studied law at the University of Havana and, in 1930, took part in student protests against the dictatorship of Gerardo Machado. Literature, however, was always his true vocation. In 1937, with the publication of his poem Muerte de Narciso, he announced an already mature poetic voice, dense with cultural references and infused with baroque-rooted lyricism.

Before establishing himself as a novelist, Lezama carried out monumental work as a cultural organizer and animator through a series of journals he founded and edited. Spanning more than two decades, this cycle functioned for him as a Renaissance-style workshop and a collective creation that, once published, “resembled a neighborhood gathering when bread comes out of the oven.”

Among these publications were Verbum (1937), Espuela de Plata (1939–1941), Nadie Parecía (1942–1944), and Orígenes (1944–1956), the crowning achievement of his editorial work. Publishing forty issues, Orígenes became the epicenter of mid-twentieth-century Cuban culture and, according to Octavio Paz, “the best literary magazine in the Spanish language.”

Lezama did not conceive these journals as mere generational outlets, but as the materialization of a poetic state capable of encompassing creators of different ages and tendencies. Orbiting around Orígenes was a constellation of essential talents: poets Cintio Vitier, Eliseo Diego, Gastón Baquero, and Virgilio Piñera; essayist Fina García Marruz; and visual artists such as René Portocarrero and Mariano Rodríguez. The magazine also served as a launchpad for figures who would later become central to revolutionary Cuban culture, including Roberto Fernández Retamar. For Lezama, the project’s supreme value lay in its choral dimension, where individual voices merged—without being silenced—into a collective creative murmur.

Rooted in a very specific historical context, Lezama’s literary production constitutes a vast territory interconnected by a highly personal poetic system, developed primarily through his essays.

From Muerte de Narciso (1937) to Fragmentos a su imán (published posthumously in 1977), his poetry is marked by hermeticism and dense imagery. For Lezama, the poet operates upon the substance of language through metaphor in search of radiant clarity. Essays such as Analecta del reloj (1953), La expresión americana (1957), and La cantidad hechizada (1970) form the theoretical backbone of his universe. In them, he elaborates key concepts such as the »imago»—the image as a germinal reality—and the imaginary eras, proposing a vision of the American continent as a space of creative possibility and resistance. His maxim, “only what is difficult is stimulating,” encapsulates this ethic of creation.

In Paradiso, a work he labored over for nearly twenty years, Lezama reached the synthesis and summit of his universe. More than a conventional novel, it is a novel-poem or initiatory experience that follows the intellectual formation of the poet José Cemí, the author’s alter ego. Its publication was a major literary event that sparked both admiration and controversy, particularly because of its explicit treatment of homosexuality in the celebrated eighth chapter. For many critics, it stands as one of the masterpieces of twentieth-century Spanish-language narrative.

Dialogical and deeply engaged with his time, Lezama’s legacy demonstrated that the baroque tradition—reread and reinvented—could serve as a powerful instrument for expressing the complexity of Cuban and Latin American experience. Within the regional context, including movements such as the Latin American Boom, his position is singular: while others turned to magical realism or critical regionalism, Lezama offered an expressive alchemy drawn from a different lineage—poetic, philosophical, and hermetic—that expanded the continent’s formal horizons. In this way, his belief that the image constitutes the reality of the invisible world resonated with authors seeking to transcend mere representation.

In its stimulating difficulty, Lezama’s work continues to challenge readers as a vast metaphysical and verbal puzzle. His legacy is that of a writer who believed, to the very end, in the power of poetry to organize the chaos of the world, constructing—brick by brick, through metaphor—a linguistic cathedral where the Cuban and the universal, the familiar and the cosmic, merge into an endless and inexhaustible narrative. As critic José Prats Sariol, a student of Lezama’s legendary Delphic Course, once summarized, Lezama’s work is a convergence of “the owl’s braid and the hummingbird’s rainbow”: the dark wisdom of tradition and the sudden, colorful flash of poetic revelation.

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez