A Curtain Rises: 128 Years Since the First Film Screening in Cuba

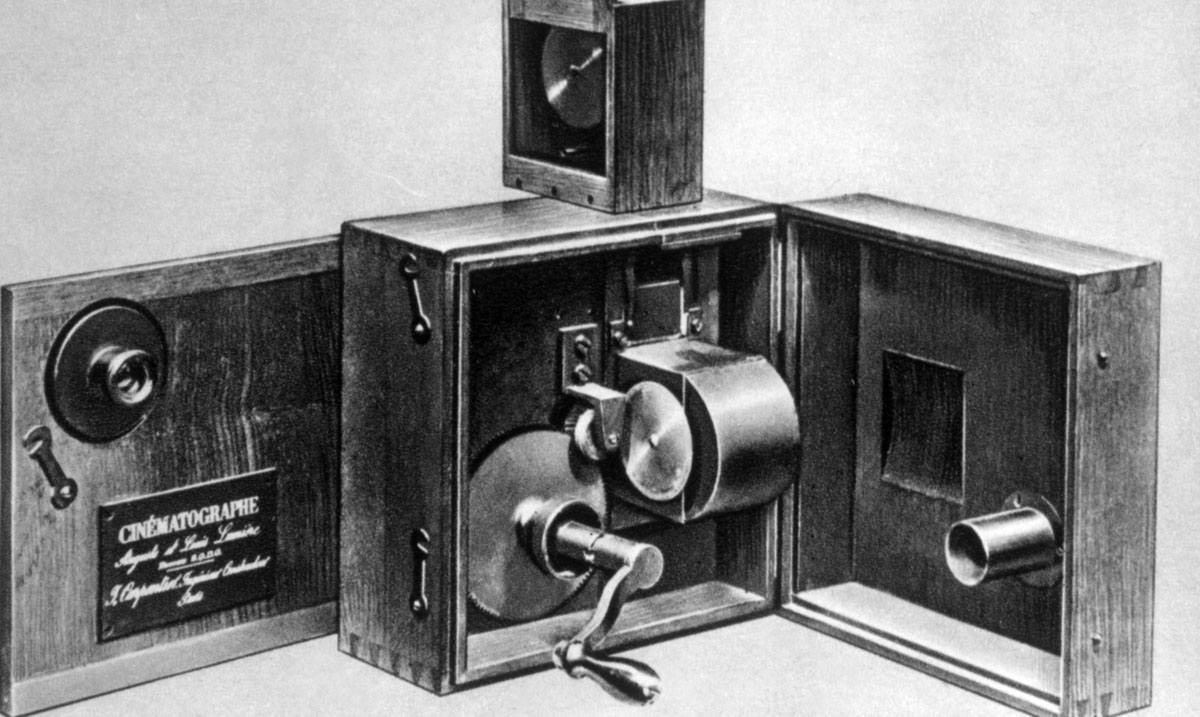

On January 24, 1897, the marvel of the century arrived in Havana. A handful of silent shorts, projected in a venue on El Prado, marked the beginning of one of Latin America’s most vibrant and complex cinematic traditions.

On January 15, 1897, the steamship Lafayette docked in Havana harbor from Veracruz. Among the impatient passengers eager to disembark was Frenchman Gabriel Veyre, a representative of the Lumière brothers. Nine days later, on Sunday, January 24, in a narrow venue at 126 Paseo del Prado, between San Rafael and San José, the magic of the cinematograph came to life before Cuban eyes for the very first time.

This fleeting event—with tickets priced at 50 cents for adults and 20 cents for children and military personnel—not only introduced a spectacle, but inaugurated a new way of seeing and narrating the island. From that moistened bedsheet that served as a screen to today’s complex narratives, Cuban cinema has been an exceptional witness to its era: a mirror of conflicts, transformations, and dreams.

Cinema arrived in Cuba at a particularly dramatic moment. The island was immersed in its second war of independence against Spain. Despite the conflict—or perhaps because of a need for escape—the technological novelty caused a sensation. According to historian Emilio Roig de Leuchsenring, the improvised venue was long and narrow, with a screen fashioned from a bedsheet sprayed with water before each screening.

The program for that inaugural evening, curated by Veyre, included a selection of short films already captivating audiences worldwide. While historical sources differ on the exact titles, among the films shown were La llegada del tren, El regador y el muchacho, Jugadores de cartas, and El sombrero cómico. The Havana audience, erupting in cries of “¡bravo!” for both the Lumières and Veyre himself, applauded so enthusiastically that some films had to be shown twice.

The fascination was captured by the press of the time. In the newspaper El Fígaro, an anonymous chronicle described how the cinematograph transported spectators to a railway station to welcome friends or to admire the skill of workers demolishing a wall. Journalist Francisco Hermida, writing in La Unión Constitucional, hailed the screenings as the only instructive, public, and daily pastime in Havana life.

Just two weeks later, on February 7, 1897, Veyre filmed what is considered the first moving picture shot on Cuban soil: Simulacro de incendio, a short documentary about Havana’s firefighters. This seemingly anecdotal event symbolized Cuba’s immediate leap from being a mere consumer of cinema to becoming a space for cinematic creation.

Cinema quickly spread across the island, though its diffusion was closely tied to complex historical circumstances. In Holguín, for instance, the first screening took place nearly two years later, on November 25, 1898, organized by occupying U.S. troops at a venue in La Periquera. This is significant: it marks the beginning of an overwhelming North American cultural and commercial influence that would dominate the coming decades.

In the shadow of this influence, Cuban cinema began developing its own identity. The first movie theaters appeared, ushering in a nascent local production characterized in its early decades by melodramas and literary adaptations.

The triumph of the Cuban Revolution in 1959 marked a radical turning point for the island’s culture, and cinema was no exception. That March, Law No. 169 established the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (Icaic), the first cultural institution created by the new government.

Icaic had a clear dual mission: to decolonize Cuban audiences’ tastes—historically dominated by American cinema—and to forge a national film industry that would both witness and participate in social transformation. Under its guidance, cinema ceased to be mere entertainment and, in the words of filmmaker Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, took on a social function.

The period from 1959 to the late 1960s is widely regarded as the Golden Age of Cuban cinema. It was a time of creative ferment, influenced by Italian neorealism and Brazilian Cinema Novo, yielding landmark works such as Lucía (1968) by Humberto Solás, Memorias del subdesarrollo (1968) by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea—considered one of the greatest Ibero-American films of all time—and De cierta manera (1974) by Sara Gómez, a sharp critique of machismo and racism.

Films such as Retrato de Teresa (1979) by Pastor Vega became cultural touchstones, portraying a woman’s struggle to balance her professional and revolutionary life with the demands of a machista husband. Later gender-based analyses have noted that, while the film’s text was progressive, its visuals and dramatic resolutions often unconsciously reproduced the very patriarchal order it sought to critique.

A qualitative leap in the representation of diversity arrived with Fresa y Chocolate (1993) by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea and Juan Carlos Tabío. The first Cuban film nominated for an Oscar, it approached intolerance toward homosexuality and the unlikely friendship between a young communist and a gay intellectual with sensitivity and courage. The film upended the cinematic norm of the heterosexual macho protagonist.

Despite progressive themes, women’s access to directing in Cuban cinema has historically been limited. From the outset, the industry was male-dominated: only nine women have directed a fiction feature in Cuban history, and none has directed a second. For many researchers, this gap reveals how power structures within the industry have been slow to change, despite progressive rhetoric.

In recent decades, the industry now stands at a crossroads, striving to preserve its rich legacy while navigating market pressures and material constraints. Nevertheless, it continues to produce works that seek to engage with the island’s contemporary realities, keeping alive the spirit of that invention which, 128 years ago, prompted a Havana audience to cry “¡bravo!” at the sight of a moving image—a new way to tell their own story.

From the moistened bedsheet on El Prado to the digital screens of the 21st century, Cuban cinema has been much more than a spectacle. It has been a restless witness, a social critic, a mythmaker, and a forum for debate on what it means to be Cuban. Its story—full of light and shadow—is, in itself, the best portrait of the complex and passionate island that gave it birth.

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez