José Luis Posada: The Critical Line That Defined an Era in Cuba

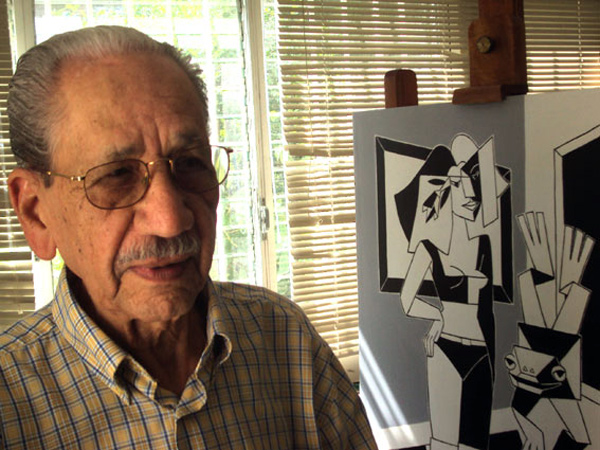

In the world of Cuban graphic arts, where politics and creativity intersect, few names resonate with the force and originality of the Asturian-Cuban artist José Luis Posada Medio. Affectionately known as “el gallego Posada,” this master of caricature and illustration, who passed away in 2002, left a void in the island’s cultural fabric and a legacy of biting wit and social commitment.

Characterized by critical expressionism and sharp humor, Posada’s work not only documented decades of Cuban life but also became a tool for collective reflection—a mirror that sometimes entertained, sometimes unsettled, but never went unnoticed.

The life of José Luis Posada is itself a narrative shaped by the great upheavals of the twentieth century. Born in Villaviciosa, Asturias, in 1929, his childhood was abruptly interrupted by the Spanish Civil War. In 1938, at just nine years old, his family fled fascist terror, crossing into France in a coal barge, only to face the horrors of refugee camps for Spanish republicans. Finally, in 1940, the family settled in San Antonio de los Baños, Cuba, where young Posada began a double life: working at the family garage by day and immersing himself in the creative world of drawing by night.

His training was unconventional and largely self-taught. A trip to New York in the early 1950s brought him into contact with the Art Students League and the dynamic world of American commercial graphics, an influence that would shape his future style. But it was in Cuba that his talent found its true purpose and distinctive voice.

The triumph of the Cuban Revolution in 1959 was a decisive turning point for Posada’s life and career. At thirty, he left the garage behind to dedicate himself fully to art, channeling his talents into the cultural project of the nascent revolution.

His crowning moment came in 1966 with the founding of El Caimán Barbudo, the magazine of the young revolutionary intelligentsia. Posada not only named the publication but also designed its iconic image: a bearded caiman that became a symbol of Cuban cultural journalism. Through its pages, Posada displayed all his genius. His illustrations and cartoons—undeniably solid and original—gave the magazine extraordinary visual dynamism. There, he created a critical “bestiary” of national and international figures, directing his incisive gaze at bureaucrats, opportunists, and political mediocrities, always with high aesthetic and communicative standards.

José Luis Posada’s work stands as a pillar of Cuban communication graphics in the latter half of the twentieth century. An admirer of German artist George Grosz, Posada absorbed his tragic, critical sensibility and fused it with Cuban humor, eliciting knowing smiles more than laughter. His expressionist style, unprecedented in Cuban graphics at the time, introduced a new strategy of visual coding that engaged an audience hungry for truth and critique.

More than a mere illustrator, José Luis Posada was a visual chronicler, a philosopher of the sketch, who—from his position as an immigrant turned Cuban by choice and conviction—interpreted the complexities, contradictions, and hopes of his era. His pencil, always sharp and precise, leaves an indelible mark on the island’s cultural memory—a graphic testament that art, even when born of satire, is a profound expression of belonging and love for the homeland one chooses.

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez

Photo: La Jiribilla