A Chinese Plum Tree Blossoms in the Caribbean

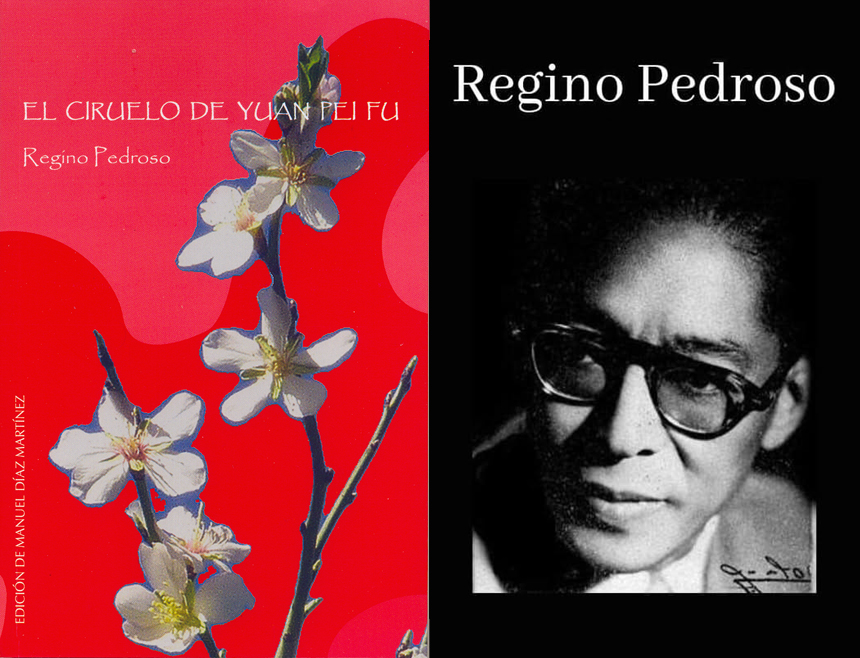

In El ciruelo de Yuan Pei Fu, Cuban poet Regino Pedroso crafts a bold cultural dialogue between Cuba and China, using the symbolic tree as a metaphor for resistance and cultural blending.

This work—extraordinary and singular in the Cuban literary landscape of the early 20th century—amplifies the voice of an author deeply committed to social struggles and the vindication of marginalized identities, particularly those of Afro-Cubans and the Chinese community in Cuba. A central figure in social and Afro-Cuban poetry, Pedroso transcends geographical boundaries to explore the universality of oppression and hope.

The plum tree—revered in Chinese culture as a symbol of perseverance for its ability to bloom in winter against the cold—becomes a powerful metaphor for anti-imperialist resistance and the dignity of the oppressed. The poem evokes the history of Chinese coolies brought to Cuba in the 19th century, exploited alongside enslaved Africans, drawing a poignant parallel between their suffering and Cuba’s struggles for sovereignty. Through natural imagery and references to workers’ uprisings, Pedroso suggests that the fight for freedom is rooted in diverse but converging traditions.

His language oscillates between avant-garde free verse and Afro-Cuban rhythms, incorporating Chinese vocabulary and Taoist philosophy. The poem’s rich imagery—snow versus tropics, silence versus drums—highlights the tension between cultures while also pointing to a possible harmony. The fragmentary structure of some poems reflects a sense of uprootedness, while recurring motifs like «blossoming in the frost» reinforce a message of resilience.

The work emerges in postcolonial Cuba during the 1930s and ’40s, a time when Pedroso, closely linked to labor and anti-racist movements, sought to reclaim the Chinese heritage as an integral part of the Cuban nation. Yuan Pei Fu’s Plum Tree embodies the immigrant who, far from home, takes root in Cuban soil. This vision challenges exclusionary nationalist narratives and proposes a mestizo, plural Cuban identity in solidarity with global struggles.

The poem draws inspiration from Yuan Pei Fu, an 18th-century Chinese poet and painter, and from the iconic plum tree—a symbol of resistance, purity, and beauty in adversity. Through a meticulous reimagining of Chinese aesthetics, Pedroso conjures not only images of Eastern landscapes but also meditates on universal themes such as loneliness, nostalgia, the fleeting nature of time, and the quest for transcendence.

Although the historical record is sparse and sometimes contradictory, Yuan Pei Fu may have actually been a 14th-century martial arts master. Despite being described as a poet and painter, it is likely Pedroso drew inspiration from Yuan Mei, a Qing dynasty poet, or perhaps from a legendary figure altogether.

More than just a poetic chronicle of the Chinese diaspora in Cuba, Yuan Pei Fu’s Plum Tree stands as an anticolonial manifesto that anticipates contemporary discourses on interculturality. By intertwining Asian symbols with Afro-Cuban roots, Pedroso constructs a revolutionary humanism where beauty and social justice are inseparable. In today’s context of mass migration and neocolonialism, the work resonates as a hymn to art’s power to unite seemingly distant worlds.

«In the snows of the East, Yuan Pei Fu planted his plum tree,

and here, among wild cane, his wood blossoms…

Roots that fear neither the axe nor the foreigner.»

Regino Pedroso Aldama, born in Matanzas on April 5, 1896, was a poet and essayist, a pioneer of social and Afro-Cuban poetry in Cuba. The son of a Chinese immigrant and a Cuban mother, his mestizo heritage shaped a body of work that fused Antillean, African, and Asian cultural traditions. Initially influenced by modernism, he evolved toward a style committed to labor struggles and anti-imperialist causes, reflecting his affiliation with the Cuban Communist Party from the 1930s onward. His notable works include Nosotros (1933), Salutación a Zúñiga (1940), and the piece under review—texts that grapple with colonial exploitation, the resistance of African-descended peoples, and intercultural dialogue.

Seen as a bridge between the avant-garde and revolutionary literature, Pedroso blended lyrical language with direct, combative expression. After the Cuban Revolution, he joined the cultural institutions of the new government and was awarded the National Literature Prize in 1981. His legacy lies in his ability to weave together marginalized identities—Afro-Cuban, Chinese, proletarian—into a poetic vision that upheld social justice as its aesthetic core. He died in Havana on October 2, 1983, leaving behind a body of work that continues to blur the lines between the local and the universal.

Although Pedroso published other works after the Revolution, the essence of his poetic voice had already soared during the republican era, with Yuan Pei Fu’s Plum Tree standing as an essential cornerstone of his legacy.

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez