A Sincere Man from Where the Palm Tress Grows

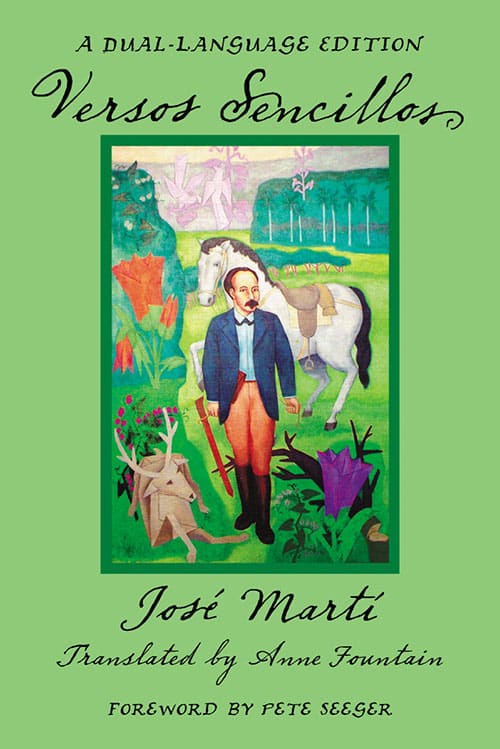

It was December 13, 1890. In New York City, José Martí gathered with a close circle of friends in one of those meetings that served as a refuge for his soul, divided between political activity and literary creation. That afternoon, probably in the intimacy of a home, the poet decided to share for the first time a manuscript containing the purest and most refined core of his thought: his original Versos Sencillos. The verses are presented literally, as Martí intended, without metaphor, preserving the authentic meaning.

This moment, beyond its apparent ordinariness, represents a milestone in Hispanic-American literature. Here, the ideologist and strategist of Cuban independence reveals himself in his most intimate and universal facet. The poems he read that day, later published in October 1891, are not only the culmination of his personal aesthetic quest but also the crystallization of a new sensibility that would help define Modernism.

Although detailed records of that meeting do not exist, several specialists highlight the context. Martí, nearly 38 years old, was undergoing a period of intense revolutionary activity and personal reflection. He had founded newspapers, written fundamental essays, and outlined the strategy that would lead to the War of ’95. Yet, amid this whirlwind, the poet sought and found a space for pure creation. The Versos Sencillos were written during a period of physical recovery and direct contact with nature, giving the work a tone of convalescence and renewed lucidity.

By sharing them with his friends, Martí was not presenting a draft but offering a lyrical confession. The choice of the adjective “Sencillos” was in itself a declaration of aesthetic and ethical principles. In an era when poetry could tend toward the grandiose or rhetorical, he opted for clarity, brevity, and authenticity as the supreme values of his art. That reading was, therefore, the first trial by fire of a collection that sought to move not through complexity but through the force of emotional truth and the precision of imagery.

Versos Sencillos holds a central place in Martí’s body of work as the meeting point of the politician, philosopher, and poet. If his previous work, such as Ismaelillo (1882), had inaugurated modernist trends with an introspective and novel language, this book represents maturity and synthesis.

The work consists of 46 poems, mostly in quatrain form, which structure an intimate and multifaceted dialogue between the author and himself, as well as the world. The themes, far from trivial despite their simple treatment, are the pillars of his worldview.

Against the vice and mask of urban life (“Del corredor de mi hotel”), Martí opposes the “eternal forest” and the “gentle murmur” of his “laurel grove.” Nature is not merely a setting but a teacher of an ethic of authenticity and freedom. The most cited and politically defining verse arises from this simplicity: “Con los pobres de la tierra / Quiero yo mi suerte echar.” This declaration, born of contemplation, irrevocably links his personal destiny with that of the oppressed. From the moving elegy of “La niña de Guatemala” to memories of friends and loves, the collection explores pain and loss with striking nakedness, showing the vulnerability of the hero.

In section V, the author offers an unsurpassed metapoetic self-definition: “Mi verso es como un puñal / Que por el puño echa flor.” Here, he encapsulates the essence of his art: a tool of struggle that simultaneously produces beauty; something useful yet sublime.

Several researchers highlight how the work also constitutes a return to traditional forms but with entirely new symbolic depth and philosophical insight. Martí does not seek formal innovation for its own sake but the most direct and thus most powerful expression of a complex worldview. The “simple” style becomes the highest sophistication: the ability to convey the essential without superfluous adornment. This transition reflects his evolution as a thinker: from proclamation to meditation, from exhortation to intimate testimony that, by its authenticity, becomes universal.

The reading on December 13, 1890, was the private birth of a public and timeless work. Versos Sencillos is the book in which Martí achieved the ultimate alchemy: fusing love of the homeland, solidarity with the dispossessed, contemplation of nature, and meditation on death into accessible, musical language.

His legacy transcends the page. The most tangible proof is that fragments of these verses, adapted to the melody of Guantanamera, became the quintessential Cuban popular hymn, sung worldwide. This singular fact—that Martí’s cultivated and deliberately simple poetry nourished the popular songbook—confirms the success of his enterprise: creating a work born from the most intimate experience that resonated in the collective heart.

Thus, that meeting with friends was not a mere social act. It was the moment when the architect of the Cuban nation revealed the foundations of his own spirit, and when the poet, after years of searching, found the serene, clear, and indelible voice that would define him for posterity: the voice of a sincere man, who, before dying, cast his verses from the soul.

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez

Photo: Cuban Cultural Center of New York