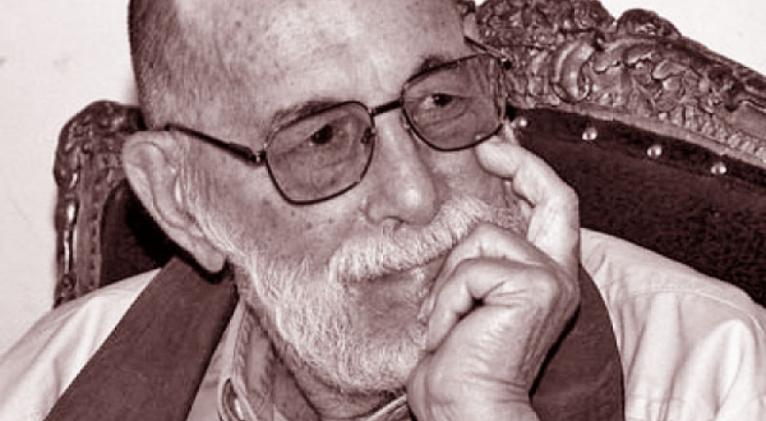

Adalberto Álvarez: The Eternal Gentleman of Cuban Son

In the landscape of Cuban music, certain names endure for their talent; others, for their character. Adalberto Cecilio Álvarez Zayas (1948–2021) achieved the rare distinction of excelling in both. Known as El Caballero del Son—the Gentleman of Son—his career was not simply a string of musical triumphs, but a lifelong commitment to preserving and reinventing the son. He championed this genre with incomparable elegance and passion.

His work became the backbone of contemporary Cuban dance music. Through his two major ensembles—Son 14 and Adalberto Álvarez y su Son—he forged an unmistakable style. As music critic Guille Vilar wrote, he made «the flowers that beautify the garden of the homeland bloom in our Cuban souls.»

Although born in Havana on November 22, 1948, his birth there was «accidental,» as his mother was visiting the capital at the time. Adalberto always considered himself a son of Camagüey, where he was registered and raised. His connection to the province would shape both his life and artistry, ultimately earning him the recognition of Illustrious Son of Camagüey.

He grew up in an exceptional musical environment. His father, Enrique «Nené» Álvarez, was a distinguished sonero who led Camagüey’s longstanding Conjunto Avance Juvenil—an ensemble where a young Bartolomé Maximiliano Moré, later known as Benny Moré, once sang. His mother, Rosa Zayas, studied music later in life and eventually joined the Camagüey Professional Choir, demonstrating the determination that would profoundly influence her son. “My greatest role model, although I admired many great musicians, was my father. I grew up in rehearsals and always wanted to be like him,” Adalberto recalled.

At just nine years old, he joined his father’s orchestra as a paila player. Between 1966 and 1972, he studied bassoon at Havana’s National School of Art (ENA) until 1975, when he also conducted the school’s typical orchestra, where he began composing and arranging, drawing inspiration from Benny Moré, Miguelito Cuní, and Félix Chapotín.

His early compositions, such as Con un besito mi amor, caught the attention of Joseíto González, director of Conjunto Rumbavana, who popularized them. The most memorable story from this period concerns the debut of El son de Adalberto. After insisting on taking the untitled song, Joseíto later sent a telegram that read: “NUMBER PREMIERED. COMPLETE SUCCESS. TITLE ‘EL SON DE ADALBERTO.’”

In 1978, seeking greater exposure, Adalberto accepted a proposal from Rodulfo Vaillant, a radio executive in Santiago de Cuba, to create a new ensemble. Thus emerged Son 14—founded in Santiago, though its members hailed from several provinces: “Between six or seven Camagüey residents, six from Santiago, and one from Guantánamo, we formed Son 14. There were actually 13 musicians, but we included the stagehand to round out the number.” The ensemble’s name was chosen by his mother, Rosa Zayas.

With pianist Frank Fernández as producer, Son 14 recorded its first LP, A Bayamo en coche (1979), under near-epic conditions: “we recorded the album in the middle of a cyclone.” The group introduced a fresh, groundbreaking sound for its era. Critic Rufus Boulting-Hodge noted that their arrangements were often “harshly dissonant, restlessly edgy, with a montuno that pushed the tempo to a pace few salsa dancers expected—or could keep up with.”

Son 14 quickly became a national and international sensation, overcoming the geographic limitations typically faced by provincial groups. Among its widely celebrated hits were A Bayamo en coche, Agua que cae del cielo, El son de la madrugada, La soledad es mala consejera—later turned into a bolero by Omara Portuondo—and “Son para un sonero.” The group toured Venezuela, Finland, Sweden, Switzerland, the United States, Canada, and Spain, carrying Cuban son to global audiences.

After five successful but family-distant years in Santiago, Adalberto left Son 14 in 1984. That same year, he founded Adalberto Álvarez y su Son, the project that would define the rest of his career. Of his departure, he explained: “I ceded the name and the leadership to the group; they continued (…) even though the name was mine, I gave it to them so they could keep working.”

The new ensemble aimed to delve deeper into the world of dance music and conquer the dancefloors. Musically, he added a trombone, reinstated the pailas and the tres, and gave greater prominence to the vocalists, echoing the ideas of Arsenio Rodríguez. Over time, the group evolved into a formation featuring two trombones and two trumpets.

This era produced some of Adalberto’s most iconic works: Y qué tú quieres que te den (nearly a religious and social anthem), El mal de la hipocresía, Para bailar casino, and Mi linda habanera.

The orchestra also served as a launching pad for singers such as Paulito Fernández (later Paulito F.G.) and collaborated with artists like Omara Portuondo, Celina González, and Pancho Amat.

Adalberto had a clear philosophy of composition: “In my music, I’ve always sought to use a universal language […] I’ve always treated lyrics with respect, never being aggressive […] and tried to ensure they carry a message.” This commitment to clarity and universality helps explain why he became “the most covered Cuban composer in the Latin world over the past 30 years.”

For him, Cuban identity was inextricably linked with his music: “It’s present in the way we speak, the way we sing, the images depicted in our songs, and what is felt when listening. You immediately know it was written by a Cuban.” He was also outspoken about the training of young musicians: “A trumpet graduate from the Higher Institute of Art in Cuba can play the most difficult music in the world, but when I hand him a score of our music, he asks: ‘Professor, explain how to do this.’”

Adalberto was among the first Cuban artists to publicly identify with Santería. His composition ¿Y Qué Tú Quieres Que Te Den? serves almost as a musical compendium of the Yoruba pantheon, “moving through the Orishas, quoting religious music, and telling the audience, according to their attributes, what to ask of each one,” as Rufus observed.

Throughout his career, Álvarez received numerous distinctions, including the National Music Prize (2008), several Cubadisco Awards (2002, 2003, 2018), the Félix Varela Order, the Distinction for National Culture, two Latin Grammys as well as five nominations, and recognition as a Master Teacher.

He deeply valued his role as an educator: “I’m fortunate to say I’ve trained musicians—both instrumentalists and singers.” His orchestra became a school for many artists who later rose to prominence in Cuban music.

Until the very end, Adalberto remained creative and committed. In his final years, he served as deputy to the National Assembly of People’s Power for Camagüey (2013–2018). He died in Havana on September 1, 2021, at age 72, from pneumonia complicated by Covid-19. His passing left an indelible void in Cuban culture.

Adalberto Álvarez embodied a rare blend of tradition and innovation: deeply rooted yet universally resonant. As Rufus Boulting-Hodge observed, «in his first five years as a bandleader and arranger, Adalberto Álvarez played a critical role in upending established norms, opening the way for others, and creating space for the increasingly well-trained Cuban musicians to showcase their skills.»

His legacy is not just the more than 40 recorded albums or the 130 songs he composed, but the living, vibrant continuity of Cuban son, modernized without losing its essence. As he put it: “When you arrive somewhere to play and see the dance floor full, that’s the moment you enjoy the most. Seeing the joy on the dancers’ faces—that is the most important moment in a musician’s life.”

For more than four decades, El Caballero del Son reigned in the hearts of Cuban dancers, leaving a trail of musicality and Cuban identity that transcends borders and generations. Today, whenever the tres rings out or the chorus of Y qué tú quieres que te den is heard, his spirit lives on, reminding us that, as he said, “A repertoire that becomes a classic must be played, because the audience demands it, regardless of who is on stage. The work itself is what matters most.”

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez