Amelia Peláez: Turning Cuban Color into Vanguard Art

Amelia Peláez del Casal was a decisive figure who forged a modern, unmistakably Cuban artistic language. As part of the island’s first avant‑garde generation, her work reflected a cosmopolitan education and became an emblem of national identity, transforming everyday objects and domestic architecture into a universal hymn to color and form. From these foundations, her artistic trajectory was marked by a constant drive for artistic exploration, stretching from her roots in Cuba to the nerve centers of international modern art.

Amelia Peláez was born on January 5, 1896, in Yaguajay. At the age of twenty, she enrolled at the National School of Fine Arts San Alejandro in Havana, where she studied under master painter Leopoldo Romañach. From him, she inherited a deep interest in color that would decisively shape her career. In 1924, she held her first solo exhibition alongside painter María Pepa Lamarque at the Association of Painters and Sculptors of Havana. Three years later, in 1927, she traveled to Paris on a scholarship, studying at prestigious institutions such as the École du Louvre and the Académie de la Grande Chaumière.

Her training took a definitive turn between 1931 and 1934, when she studied with Russian artist Alexandra Exter. Exter introduced her to color theory, abstraction, and avant‑garde design—lessons that Peláez herself acknowledged as fundamental to her greatest technical advances.

In 1933, she successfully presented 33 works—still lifes, landscapes, and portraits—at the Zak Gallery in Paris. The exhibition confirmed her status as a mature, fully professional artist.

When she returned to Cuba in 1934, Peláez was already fully formed as an artist. It was, however, in her homeland that she found her definitive voice and joined the Cuban artistic avant‑garde, a movement committed to defining a national cultural identity through art.

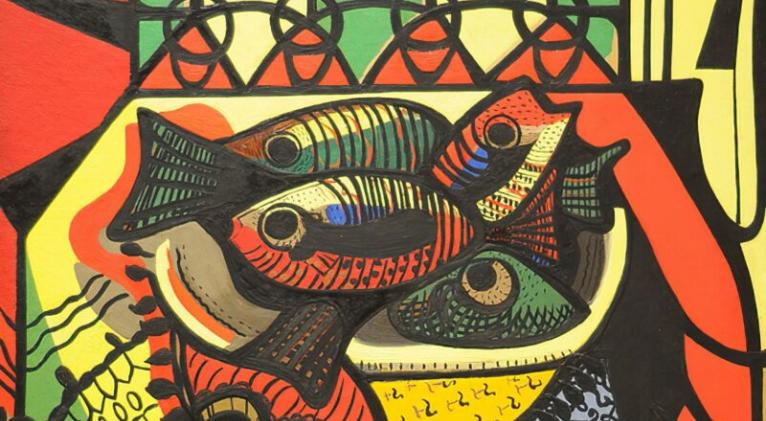

From the 1940s onward, tropical fruits such as mamey and soursop became a central axis of her painting. These still lifes were not simple depictions but carefully structured compositions that explored the possibilities of color and form. Her Interiors of El Cerro series captured the essence of Havana homes—their furniture, stained‑glass windows, and iron grilles. She transformed these architectural and decorative elements into a dense weave of lines and flat color fields that define her most recognizable style. In works such as Las Dos hermanas (1943) and Mujer (1945), she portrayed women with a presence that shifts between the grotesque and the dramatic, drawing on European avant‑garde aesthetics to offer a singular visual perspective.

Her work evolved from analytical Cubism toward compositions dominated by bold black outlines enclosing luminous, flat areas of color, edging toward geometric abstraction in the 1950s. Yet her creative practice was never limited to painting. Beginning in 1950, she devoted several years to ceramics in a workshop in San Antonio de los Baños. She also left an important legacy in mural art, including the ceramic façade of the Habana Libre Hotel (1958) and the mural for the Court of Auditors in Havana (1953).

After her successful exhibition at the Lyceum in Havana in 1935, her work began to travel to leading galleries and institutions. Highlights include her retrospective at the National Museum of Fine Arts in Havana in 1967 and her participation representing Cuba at major international events such as the Venice Biennale and the São Paulo Biennial.

Amelia Peláez died in Havana in 1968, but her art remains vibrantly alive. Her greatest contribution was to demonstrate that local traditions—colonial stained glass, backyard fruit, the design of an iron grille—could be synthesized into a modern, universal visual language. She opened the way for subsequent generations of Cuban artists to explore their identity without renouncing contemporaneity.

Her house‑studio in the La Víbora neighborhood, Villa Carmela, both witnessed and inspired much of this creative process. In its rooms and gardens, she achieved a kind of alchemy: distilling the essence of the everyday and transforming it, through compositional rigor and a vibrant palette, into an artistic legacy that today defines a fundamental strand of Cuban visual culture.

For curator Roberto Cobas Amate, Peláez’s work stands as a monument to the defense of Cuban cultural identity: “Grounded in these roots, she knew how to project them into a universal language of singular unity. Her evolution unfolds without abrupt breaks, in a continuity affirmed by her determination to remain true to herself, without detours or repetition.”

On the anniversary of her birth, she is remembered not only as a great painter, but as a creator who taught us to see the island with new eyes—where the decorative becomes essential, and color speaks with a voice of its own.

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez