An Uprising to Awaken a Nation: July 26

The Cuban people could no longer endure the abuses inflicted upon them. Since Fulgencio Batista’s coup in 1952, which shattered constitutional order and imposed a dictatorial regime, the country had plunged into a deep moral and material crisis.

Repression became systematic. The progressive 1940 Constitution was abolished, political parties were banned, and strict censorship of the press was imposed. Members of the suspected opposition were relentlessly hunted down by the notorious Military Intelligence Service (SIM).

Corruption became institutionalized. While Batista and his inner circle amassed fortunes through deals with the American mafia, the majority of the Cuban populace lived in poverty. In rural areas, half of all children suffered from parasites and anemia. Farmers lacked basic resources and were frequently evicted to make way for foreign corporations, which controlled 75 percent of the country’s arable land.

In towns and cities, conditions were equally dire. Ninety percent of public services were in the hands of U.S. companies, and nearly 30 percent of the population faced unemployment. State health and education services were grossly inadequate.

Faced with this reality, Fidel Castro—a young lawyer educated at the University of Havana—concluded that the political path had been exhausted. Inspired by the ideals of José Martí, he chose the route of armed struggle. He would later declare, “Martí was the intellectual author of July 26. He taught us that freedom is not begged for; it is won with the edge of the machete.”

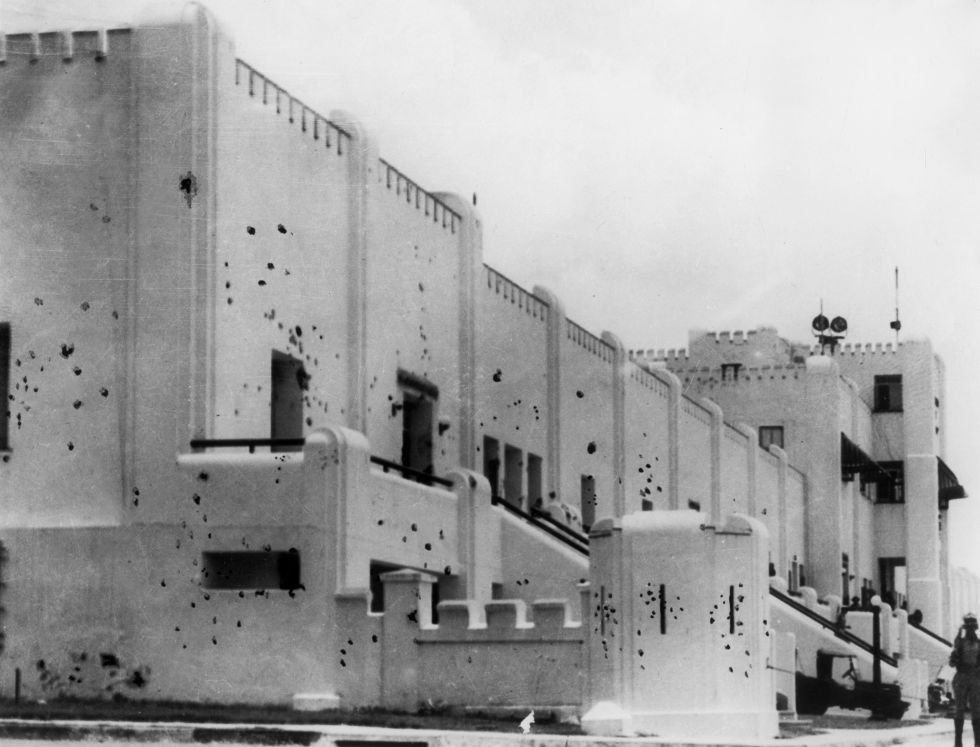

Fidel carefully selected military targets: the Moncada barracks in Santiago de Cuba and the Carlos Manuel de Céspedes garrison in Bayamo, which were the second and third most important fortresses in the country.

A group of 160 young people—mostly workers, farmers, and students under the age of 30—along with two women, Haydée Santamaría and Melba Hernández, prepared to lay down their lives to free the nation from tyranny.

This was only the beginning of a war for liberation. One of the goals of the assault was to seize weapons; the other was to ignite a national uprising. “We knew it was almost a suicide mission, but Cuba needed to be shaken from its slumber. As Martí said, ‘A just principle from the depths of a cave can do more than an army,’” Melba Hernández would later recall.

The battle turned out to be one-sided. The element of surprise was lost, and the revolutionaries’ weapons were inferior in both caliber and firepower. The repression that followed was brutal. Batista ordered that for every soldier killed, ten revolutionaries should die. Most of the wounded or captured were tortured and murdered to meet that quota.

However, the blood spilled and the suffering endured by those young revolutionaries were not in vain. The revolution had begun—and it could no longer be stopped. As Fidel Castro would later say, July 26 was “the small engine that started the big one.”

Though a military failure, the July 26, 1953 attack exposed Batista’s true nature. The regime’s savage repression provoked international outrage and mobilized previously apolitical sectors of Cuban society. The attack became a powerful symbol of resistance. The future guerrilla nucleus, formed in exile in Mexico, would go on to adopt the name “26th of July Movement” (M-26-7).

“Moncada taught us how to turn setbacks into victories. It wasn’t a defeat; it was a spark,” Fidel Castro said in 1963.

As Cuba’s national poet Nicolás Guillén wrote: “Martí promised it, and Fidel fulfilled it.” On October 14, 1960, the Council of Ministers passed the Urban Reform Law and the Law on Vacant Lots and Recreational Estates. With these two landmark acts, the Revolutionary Government declared that it had fulfilled the Moncada Program, addressing six fundamental problems inherited from the neocolonial period: land ownership, industrialization, housing, unemployment, education, and public health.

Today, as Cuba continues to suffer under the United States’ inhumane policies, we must honor the memory of those young men and women who did not hesitate to give their lives for the nation’s freedom. The struggle is not over; we continue to work toward a better future.

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez