Antonio Bachiller and the Guardianship of Knowledge

On June 7, 1812, Antonio Bachiller y Morales was born, known today as the father of Cuban bibliography. His works, such as works such as Apuntes para la historia de las Letras and de la instrucción Pública en la Isla de Cuba, offered a remarkable demonstration of his investigative skill and lifelong dedication to knowledge. As a university professor, historian, journalist, and legal scholar, Bachiller y Morales set a foundational precedent for bibliographic studies in both Cuba and Hispanic America. His contributions also extended to free trade, the challenges of Cuban agriculture, and the socioeconomic aspects of the transatlantic slave trade, in which he defended the moral unity of the races from a liberal standpoint.

Forced into exile in the United States from 1869 to 1878 due to unfounded suspicions against his family, following the events at the Villanueva Theatre and the Café del Louvre—Bachiller maintained correspondence with El Siglo XIX. In this Mexican newspaper, he chronicled the early stages of Cuba’s Ten Years’ War.

“Alongside other intellectuals, he called for broad autonomy for Cubans as the only way to end the war. Following the incidents at the Villanueva Theatre and the Café del Louvre, Spanish colonial authorities deemed him a suspect. As a result, his home was raided and ransacked by members of the Spanish Volunteer Corps. In that violent episode, he also lost his invaluable library. After suffering harassment and abuse targeting his family, his property, and himself, and facing relentless persecution, he was forced to emigrate with his entire family to the United States in early 1869, shortly after the war began. He was only able to return to his homeland after the signing of the Pact of Zanjón in 1878,” recounted intellectual and researcher Dr. Armando Hart.

His writings—firmly rooted in the realities of his time and leaving a lasting legacy—were featured in most of the leading publications of the Cuban archipelago and abroad. While in the United States, one of his standout articles, Cuba, appeared in Appleton’s Magazine. Among his other notable works are Elementos de la Filosofía del Derecho (also known as Course in Natural Law), La Habana en dos Cuadros, and Matilde, or the Bandidos en Cuba.

“His work became the fertile lifeblood that nourished the bibliographic endeavors of disciples and successors at the close of the 19th century, blossoming in the early 20th century with the monumental achievements of Carlos Manuel Trelles y Govín, and shining brighter than ever from 1959 onward with the initiatives of the National Library of Cuba,” highlights researcher Araceli García Carranza.

According to Hart, “Bachiller’s boundless erudition stemmed not only from his extraordinary talent but also from his rigorous academic training. He was educated at the Seminary of San Carlos and San Ambrosio in Havana, as well as the University of Havana and other prestigious educational institutions across the country, where he attained a truly outstanding formation.”

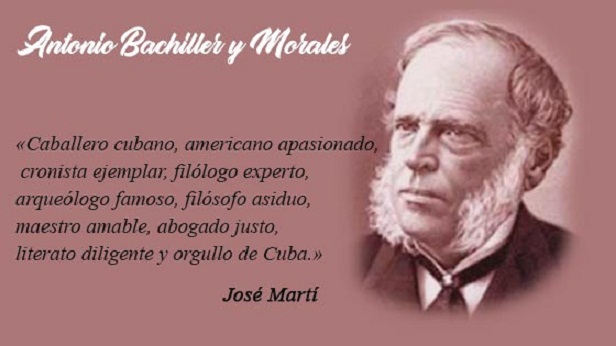

Cuban national hero José Martí also praised Bachiller y Morales’s scholarly virtues, which stood in stark contrast to the oppressive realities of the time and to the destiny of Cuba itself:

“A passionate American, exemplary chronicler, expert philologist, renowned archaeologist, tireless philosopher, just lawyer, kind teacher, diligent man of letters—Bachiller y Morales was a source of pride for Cuba and a credit to his race. But more than for his tireless labor, the key to all his other virtues; more than for that encyclopedic knowledge that turned his capable mind into something of an Alexandrian library; more than for his moral clarity, which in grim times—with the master’s boot on his brow—kept him engaged in researching Cuba’s and America’s hidden curiosities as if in a domestic task, seeking ways to be useful; more than for his unique blend of sincerity and respect in defending his views, and the gentle brilliance with which he treated the most stubborn novice and the humblest child as friends of the heart; more than for the eternal youthfulness preserved in his intellect by his thirst for knowledge and the purity of his life—Bachiller was remarkable because, when he could have abandoned his country or simply followed it through a crisis for which his peaceful character, generous philosophy, fondness for privilege, mistrust of struggle, and habits of wealth left him ill-prepared, he left his marble home with its fountains and flowers and books, and, accompanied only by his wife, went to live with honor where eyes offer no greeting, where the sun does not warm the elderly, and where snow falls.”

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez

Photo: 5 th September