Emilio Roig and the Reclamation of Cuban History

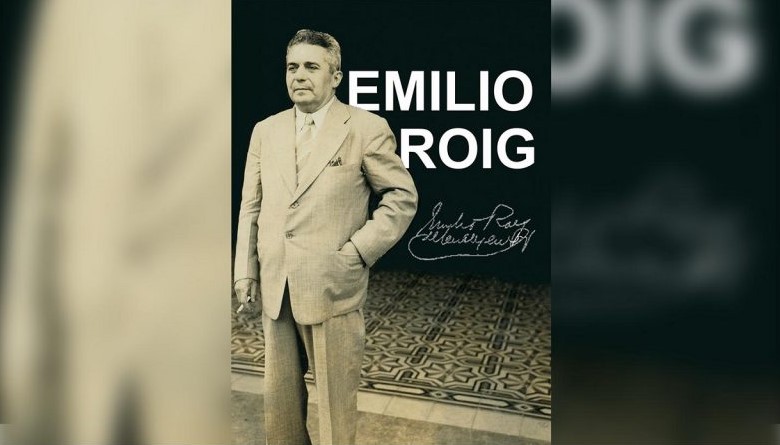

On July 1, 1935, Emilio Roig de Leuchsenring was appointed as the City Historian of Havana. At the time of his appointment, Dr. Roig was a mature man, nearing 46 years old—having been born on August 23, 1889, at Calle Acosta No. 40 in the Havana neighborhood of Belén. He was already a recognized figure in Cuban literature, law, and historiography, enjoying immense prestige among his contemporaries for his unwavering nationalist and anti-imperialist political convictions, as noted by Dr. Félix Julio Alfonso López.

Dr. López remarked, “He was a man who held deep respect for history as a science. He worked to preserve everything from the past that could possibly be saved. That inspired his studies on Heredia, Avellaneda, Narciso López, and all the great events of our past—even its most intricate details.” Eusebio Leal, who would later succeed him as Havana’s City Historian, echoed these sentiments.

Roig’s legacy is rooted not only in his tireless efforts to rescue Cuba’s national history but also in his commitment to preserving the cultural heritage intertwined with it. This commitment stood in stark contrast to the intellectual climate of his time.

With a deep love for Cuba, Roig fought to safeguard the Church of Paula and the San Lázaro quarries and opposed the destruction of the Convent of Santo Domingo. In 1938, he established the Office of the City Historian, followed by the Commission on Monuments, Historic and Artistic Buildings and Sites of Havana; the National Board of Archaeology; the Museum of the City of Havana; and the Cuban Society for Historical and International Studies. The latter organized the First National History Congress in 1942, a series that continued across various Cuban cities until 1960.

Dr. Félix Julio noted, “Roig’s prestige, tremendous work ethic, and unifying spirit brought together the finest minds in Cuban, Latin American, and international historiography during these congresses—free from ideological, religious, political, or associative discrimination. The Cuban Society for Historical and International Studies was a private, non-governmental institution, keeping it independent of partisan interests or allegiance to ruling authorities.”

Each of the National History Congresses was presided over by a prominent intellectual or historical figure from the Cuban independence movement, beginning with Don Fernando Ortiz, the patriarch of Cuban social sciences and cultural studies, from October 8 to 12, 1942, and concluding with distinguished professor Fernando Portuondo del Prado, from February 5 to 10, 1960.

In 1950, Roig convened the Meeting of Caribbean Anthropologists and was a full member of the National Board of Archaeology and Ethnology. He was also a founding member of the Society for Afro-Cuban Studies established by Fernando Ortiz. Roig authored numerous publications dedicated to rescuing and preserving the history of Havana, including La Habana de ayer, de hoy y de mañana (1928) and a series of costumbrista articles published in magazines and newspapers such as El Fígaro, Gráfico, Carteles, and Social. Eusebio Leal remarked that these writings showcased Roig’s engaging and direct style, which remains part of his inexhaustible creative legacy.

He led the initiative to publish the first Cuban edition of La Edad de Oro in 1932, preceded by his studies on José Martí. In 1935, he published Historia de la Enmienda Platt, a critical interpretation of Cuba’s political reality. Later, he compiled and edited the Actas Capitulares del Ayuntamiento de La Habana and Historia de La Habana, both distributed free of charge and released in 1938 during the inauguration of the Biblioteca Histórica Cubana y Americana Francisco González del Valle.

“He was also a driving force behind the most important scientific societies dedicated to historical research,” Leal added. “That’s why I always think of Historia de la Enmienda Platt, Tradición antiimperialista de nuestra historia, and, most of all, his brilliant 1953 essay Cuba no debe su independencia a los Estados Unidos. I believe his greatest contribution was fostering a strong anti-imperialist tradition, a sense of national sovereignty, and an approach to history that was fearless and unflinching.”

Therefore, celebrating Roig’s legacy requires action. It’s not enough to mention his name in passing when recalling isolated events or outdated anecdotes. Roig was not just a figure of the past. As the poet and storyteller Víctor Casaus eloquently put it, “A defender of cultural heritage, historian and teacher of historians, activist and creator, editor and essayist—ever the journalist—Emilio Roig was one of those rare figures who, through life and work, against all odds, gave shape to the dreams behind the birth of Cuba’s modern revolutionary awareness.”

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez

Photo: La Jiribilla