Ernesto Lecuona and the Symphony of the Cuban Soul

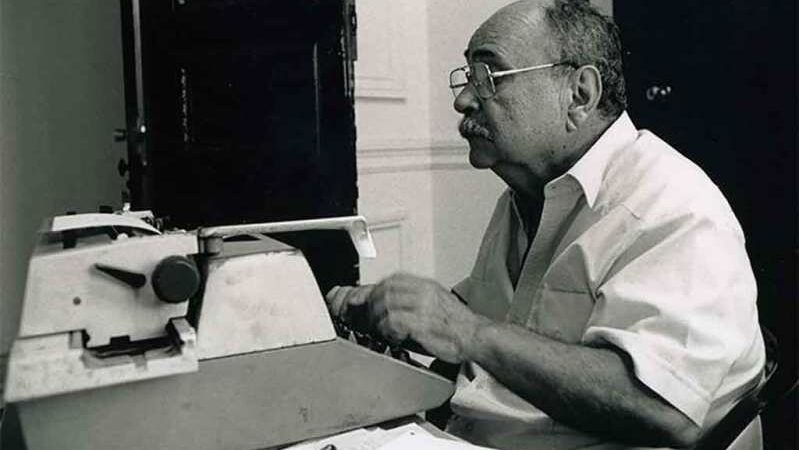

Ernesto Sixto de la Asunción Lecuona Casado was born on August 6, 1895, in Havana’s Guanabacoa neighborhood—a child destined to channel the emotional depths of an entire nation through his music. According to popular lore, a beggar woman visited his cradle as an infant and, in a moment of prophecy, declared him a genius. The prediction proved spot on. By five, Ernesto was already giving his first piano recital, initially guided by his sister Ernestina; at thirteen, he had composed his first work, the military march Cuba y América. This extraordinary precocity marked the start of a remarkable career that would gift Cuba and the world some of Ibero-America’s most enduring melodies.

Lecuona graduated with a gold medal in piano performance from the National Conservatory of Havana at sixteen. He continued his studies in France under the tutelage of Maurice Ravel, yet his heart remained firmly anchored in Cuba. As musicologist Cristóbal Díaz Ayala put it, he became “the paradigm of the fusion of the Spanish and African strands of Cuban music.” Lecuona’s ability to blend contrasting cultural elements while preserving their authentic origins would define his entire body of work.

His international career took off in 1916 with his debut at New York’s Aeolian Hall, opening the way to the Americas and Europe’s most prestigious stages. In 1924, he undertook his first tour of Spain with violinist Marta de la Torre. His subsequent piano recitals at Paris’s Salle Pleyel in 1927 and 1928 coincided with a burgeoning global fascination for Cuban music. Amid this creative ferment, Lecuona proved himself equally at home moving between popular and classical traditions, between dazzling entertainment and sophisticated composition.

A key institutional milestone occurred in 1922 with the founding of the Havana Symphony Orchestra. Yet perhaps his most popular initiative was the creation of the Lecuona Cuban Boys in 1932—the first Ibero-American orchestra to introduce Afro-Cuban rhythms in the United States. For over forty years, the ensemble charmed nightclub audiences worldwide, becoming an emblem of Cuban music’s global reach.

Lecuona’s creative spark burned with astonishing productivity. It’s said he could compose five songs in a single day. His catalog is staggering: 406 songs, 176 piano pieces, 53 theatrical works, 31 orchestral compositions, and 13 film soundtracks. Despite such volume, the quality and depth of his work never wavered, ranging from ephemeral melodies for silent cinema to intricate symphonic structures.

His output is foundational to the major achievements of Cuban and Ibero-American pianistic literature. As a performer, Lecuona could render great works of the global repertoire with such brilliance that, after hearing him play Malagueña, Arthur Rubinstein exclaimed: “I do not know whether to admire his pianistic talent or his sublime artistry as a composer more.” His skillful left-hand technique was particularly noted.

Among his outstanding piano compositions are Suite Andalucía, which includes the world-renowned Malagueña; Danzas Afro-Cubanas, a set of six pieces including La comparsa; Rapsodia Negra para piano y orquesta; and Suite Española. These pieces explore Caribbean rhythms and melodies while incorporating early 20th-century European refinement, evoking the styles of Debussy, Chopin, and Liszt.

Alongside Gonzalo Roig and Rodrigo Prats, Lecuona formed the key triumvirate in Cuban lyric theater, particularly in the zarzuela genre. His most significant theatrical achievement was the definitive formulation of the Cuban romantic ballad, also known as a romanza. Masterpieces such as María la O, Rosa la China, El Cafetal, and El Batey not only triumphed in Cuba but were the only Latin American zarzuelas to enter Spanish theater repertoires.

In Cuba, which had sidelined African musical influences, Lecuona embraced African rhythmic patterns, as evident in titles like Danza de los ñáñigos, affirming the rich legacy of Afro-Cuban culture. “I believe it is fair to note that my black dances initiate the Afro-Cuban tradition. I was the first to bring the conga drum to the score and the keyboard,” he proudly declared. Far from boastful, he was right: his Danzas Afro-Cubanas (1929–1934) were the first 20th-century concert works to conscientiously and deliberately engage the Afro-Cuban theme.

La comparsa, composed when Lecuona was only seventeen, exemplifies this innovation best. In this miniature masterpiece, he was first to notate African-derived rhythmic elements—marking the left-hand motif as an «Imitation of a drum.» The piece vividly evokes a carnival parade approaching, passing the listener, and receding into the distance.

The aesthetic Lecuona pioneered was no mere folkloric citation, but a refined stylization of popular essence. His music erased rigid social boundaries, incorporating into the concert hall the rhythms and sonorities that had been marginalized due to their association with Cuba’s popular and Afro-Cuban classes.

Beyond his artistic brilliance, Ernesto Lecuona was remembered by peers as a modest and generous man, ever ready to help those in need. Biographer Orlando Martínez called him “a man with enormous yet delicate hands, lion’s claws wrapped in silk”—a metaphor blending the power and softness that defined both his personality and artistry.

Lecuona’s kindness helped launch the careers of other great Cuban artists such as Esther Borja and Bola de Nieve. Years later, Chucho Valdés fondly recalled how, as a teenager, playing Malagueña for Lecuona brought warm encouragement: “Study hard—you’re on the right path.”

Among his quirks: he refused to fly, detesting airplanes, and was a passionate carpenter, personally supervising all home carpentry work. His favorite singer, Esther Borja, said, “he loved the bohemian life, and his doors were always open to artists, friends, and anyone who sought him out.”

On November 29, 1963, Cuban music lost one of its greatest composers, as Ernesto Lecuona died in Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain. His legacy continues to inspire contemporary Cuban musicians far beyond the classical repertoire. Siboney, Malagueña, and Siempre en mi corazón—the last of which was an Oscar nominee in 1942—are now staples of the Latin American canon, reinterpreted by artists worldwide across various genres.

Throughout his life, Lecuona balanced his gifts as a classical performer and concert composer with a flair for popular melodies. His deep knowledge of and love for Cuba’s Spanish and African roots enabled him to create a musical corpus that still gives eloquent voice to the soul of Cuba, projecting it to the world with authenticity and universality.

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez