Esteban Salas: The Foundation of a Cuban Sound

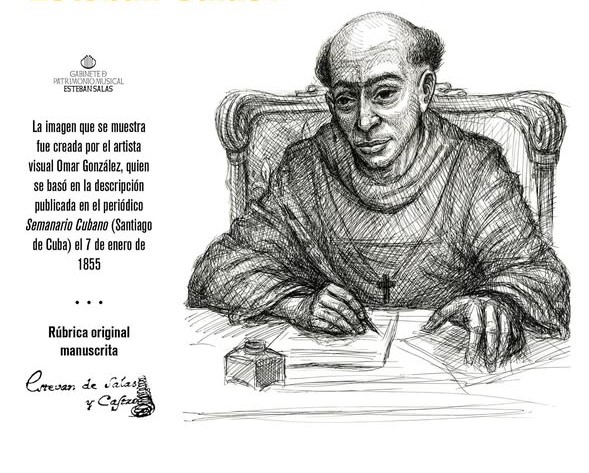

In the music hall of the Cathedral of Santiago de Cuba, a man of rugged appearance and forceful voice once directed his choristers with relentless determination. Writer Alejo Carpentier, in his novel The Kingdom of This World, portrays him as a gruff, dark-skinned, shouting old man, intent on bringing the voices in one by one, having some singers repeat what others had sung before. This conductor, Don Esteban Salas, was far more than a mere chapel master. He was an innovator who, in the eighteenth century, laid the foundations of Cuban art music, and whose legacy—rediscovered centuries later in a cathedral cupboard—now resonates in conservatories, international festivals, and award‑winning recordings.

Esteban Salas y Castro was born in Havana on December 25, 1725, into a family of Canary Island origin. From a very early age, music became his language. By the age of nine, he was already studying organ and violin, and sang as a treble in the choir of the city’s main parish church. Later, at the Seminary of San Carlos and San Ambrosio, he completed a solid education in philosophy, theology, and canon law, while refining his knowledge of counterpoint and composition.

The course of his professional life changed in 1764, when Bishop Pedro Agustín Morel de Santa Cruz appointed him interim chapel master of the Cathedral of Santiago de Cuba. Upon arriving in the eastern city, Salas inherited a modest ensemble of fourteen musicians: three sopranos, two altos, two tenors, two violins, a violone, two bassoons, a harp, and an organ. With determination, he set about expanding it, securing salary increases for his performers and incorporating new instruments such as flutes, oboes, clarinets, horns, and violas. By 1765, he had already added two horns and two oboes, transforming the chapel into a respectable ensemble for its time.

For nearly four decades, in addition to his musical duties, Salas served as a professor of philosophy, moral theology, and music at the Seminary of San Basilio Magno. It was not until 1790, at the age of sixty‑four, that he was ordained a priest, in a ceremony held at the Church of Dolores, for which he composed a villancico and a fourteen‑movement Stabat Mater. Until his death in Santiago de Cuba on July 14, 1803, his life unfolded between musical direction, teaching, and ecclesiastical service.

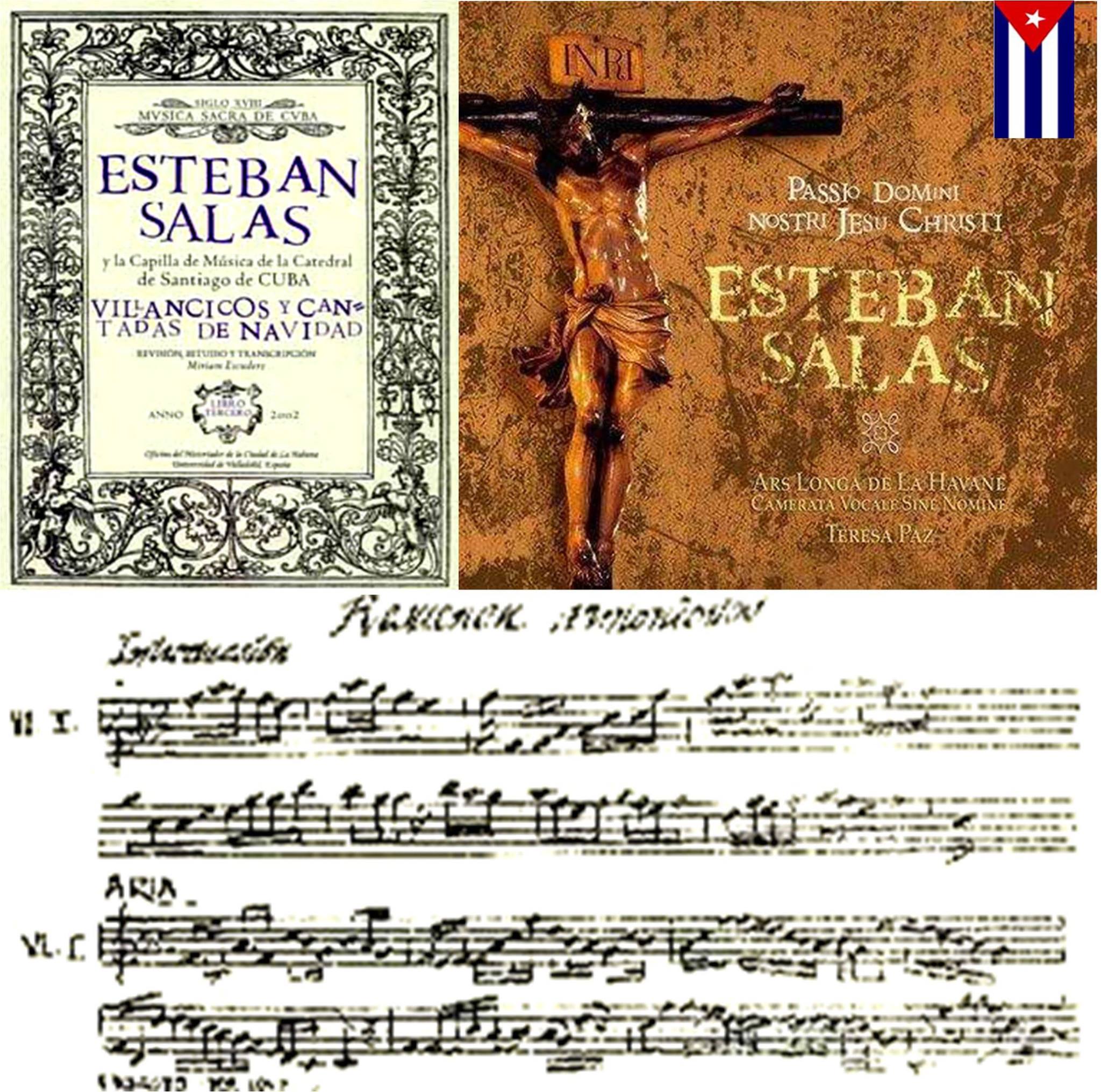

The catalogue of Esteban Salas is vast and diverse, comprising more than one hundred liturgical works, including masses, salves, motets, hymns, autos sacramentales, and passions. As several scholars have noted, his musical language is baroque, characteristic of the Latin American colonial period, yet marked by a distinctive stamp. This singularity is especially evident in his villancicos, Spanish‑language compositions that constitute one of his most significant contributions.

Dated between 1783 and 1802, these works were written for the Christmas festivities of each year. In them, the composer employed a ternary structure alternating refrains and verses, combining choral passages with solo sections. Beyond their formal design, however, their content reflects the reality of his surroundings. A paradigmatic example is Una nave mercantil (1791), composed during a severe famine in Santiago de Cuba, exacerbated by earthquakes and hurricanes. Its text expresses stark desolation: “for hunger consumes us and drains our breath.” Others, such as Pues la fábrica de un templo (1783) or Un musiquito nuevo (1797), reveal his deep devotion and evangelizing intent, using music as a vehicle for joy and praise.

Salas’s innovation, however, was not limited to expressive matters. In a gesture that modern musicology regards as a remarkable anticipation, he rejected Italianate conventions when indicating the character of his pieces. In his scores, instead of writing adagio or allegro, he used Spanish terms such as “despacio” or “alegre”—a choice that affirmed the local language within a field dominated by European traditions.

Despite his prolific output, the work of Esteban Salas fell into near‑total oblivion after his death. His name was omitted from bibliographic dictionaries and historical studies for more than a century. The recovery of his legacy began in the 1940s, thanks to the efforts of writer and musicologist Alejo Carpentier. In his foundational essay La música en Cuba, Carpentier brought Salas’s importance to light, considering him an essential figure in establishing stylistic characteristics and musical disciplines in Cuba.

Carpentier’s work sparked a process of recovery that continues to this day. In recent decades, Cuban musicologists have made fundamental contributions. Pablo Hernández Balaguer undertook an in‑depth analysis of Salas’s oeuvre and highlighted his technical mastery. Undoubtedly, however, the most ambitious project has been led by musicologist Miriam Escudero Suástegui, who devoted a decade to research in the archives of the Cathedral of Santiago de Cuba. Her doctoral and editorial work enabled the publication of 106 complete works by Salas and offered, for the first time, a systematic view of his output.

This musicological recovery has gone hand in hand with a revitalization of performance practice. Cuban ensembles such as the Coro Exaudi (conducted by María Felicia Pérez) and the group Ars Longa (under the direction of Teresa Paz) have recorded albums devoted entirely to Salas. These recordings are not merely exercises in musical archaeology; they have earned major accolades, including the 2003 Cubadisco Grand Prize, awarded to the recording Cantus in Honore Beatae Mariae Virginis, performed by Ars Longa.

For musicologist Clara Díaz, that distinction meant far more than recognition of the unquestionable excellence of a musical product. It was the result of collective efforts to preserve the nation’s oldest musical heritage.

Today, the imprint of Esteban Salas is tangible within Cuba’s institutional cultural life. In Santiago de Cuba, the Esteban Salas Conservatory trains new generations of musicians. In Havana, his name identifies the Musical Heritage Cabinet of the Colegio Universitario San Gerónimo de La Habana, a research center dedicated to the preservation, digitization, and study of historical musical sources. Founded in 2012 under the auspices of the Office of the City Historian, this Cabinet—directed by Miriam Escudero—oversees the study of diverse documentary sources related to musical practice through a multidisciplinary team.

Its director explains that the Cabinet’s mission is to “syncopate” music, because that essence of disrupting monotony and provoking movement constitutes the very core of Cuban identity. The Cabinet is also an active cultural agent and plays a leading role in organizing the international Habana Clásica festival.

Scholar Rafael Salcedo regards Salas’s music as the most complete and refined body of sacred music produced on the island. More than a composer of the past, he was a founder—a master whose search for a language of his own, rooted in his time and his land, resonated powerfully enough to be heard, studied, and celebrated centuries later, with the force of a revelation.

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez

Photo: Gabinete de Patrimonio Musical Esteban Salas