Félix Varela and the Guide to Justice

José de la Luz y Caballero described him as the first to teach others how to think. A Cuban priest, writer, teacher, politician, and philosopher, Félix Varela embodied both intellectual brilliance and extraordinary clarity, laying the groundwork for the spirit of independence that emerged in the second half of the 19th century. While Varela taught us how to think, it is worth noting how often something he opposed-blind and opportunistic praise of homeland and religion-has become an essential trait for those who, from fragmented perspectives, have sought to honor his legacy over time.

Understanding his relevance, however, is not a difficult task. One need only read his reflections – meticulous and crystal clear – to grasp the greatness of a man who saw civic responsibility as a fundamental duty. He advocated for a better society by defending individual freedoms and encouraging a diversity of opinions, and he was firmly committed to educating the population.

«Varela’s expository thought is characterized by a striking precision. He remained creatively faithful to the norms of his time in terms of writing style, influences, logical structure, and the persuasiveness of his explanations. Unlike Luz, his approach favored structured and logical teaching over abstract theorizing. His philosophical method is distinguished by its logical foundations and profound reflections. The originality of his discourse is evident, and his unique style is revealing,» explains researcher Rigoberto Pupo, who also highlights Varela’s philosophical approach as one closely linked to scientific inquiry.

In this context, his opposition to scholastic teaching, his insistence on teaching in Spanish instead of Latin, and his use of experiments and modern methods in disciplines such as physics and chemistry only scratch the surface of his vast academic contributions. Works such as the Miscelánea Filosófica and the widely acclaimed Lecciones de Filosofía demonstrate the breadth of his intellectual pursuits. The resurgence of absolutism following the coronation of Fernando VII not only endangered Varela’s life, but also led to his exile and interrupted a career that had made him one of the most progressive voices of his time at the Spanish courts.

Even in exile, his writings remained powerful. Varela was not a political agitator – he was a teacher, an educator. His influence endured through publications such as El Habanero and one of the most remarkable essays of early 19th century Cuba: Cartas a Elpidio sobre la impiedad, la superstición y el fanatismo y sus relaciones con la sociedad (1835).

«The independentist journalism of El Habanero began to have a significant impact on Cuba’s educated youth, most of whom had been Varela’s students in the philosophy and constitutional classes at the San Carlos and San Ambrosio seminaries. Although he never explicitly advocated armed struggle, he did not reject it outright. This led to what could be considered the guiding principle of his political thought: ‘Think as you wish, act as necessary’ (…) and from this doctrine emerged moral values such as prudence, dignity, responsible freedom, and collectivism,» according to researcher and university professor Emilio Antonio Borrero Ramírez.

At the core of his philosophy was an unwavering commitment to justice, intertwined with dignity and honor, both in his ideas and in their practical application in his teaching and political thought: Think as you wish, act as you need’ (…) And from this doctrine emerged moral values such as prudence, dignity, responsible freedom and collectivism,» explains researcher and university professor Emilio Antonio Borrero Ramírez.

At the core of his philosophy was an unwavering commitment to justice, intertwined with dignity and honor, both in his ideas and in their practical application in his teaching and political thought. His writings reflect this conviction: «The weapons of slander degrade those who wield them and honor those who endure their blows (…) It is easier to dismiss than to respond (…) A society in which individual rights are respected is a society of free men (…) The cruelest form of despotism is that which operates under the guise of freedom.» His essay Máscaras políticas, published in El Habanero, exemplifies these beliefs.

«Varela overturned conventional wisdom. First, in what would become known as epistemology and ideology, where the fundamental question was the origin of ideas. And he did so with a single guiding thought: to free Cuba from all forms of oppression,» explains researcher Alicia Conde Rodríguez, who adds:

«From his first writings to his last, Varela remains ours. His unwavering principles, his civic honesty, his generous and pure humanity, his profound philosophical and political insight, and his patriotism – even in the most difficult times for Cuba and for himself – make him ours forever.

Cuban journalist and scholar Julio García Luis, in an analysis of Varela’s publications, reflects on his strategic and realistic approach to history: «(…) It is characterized by the idea of understanding Cuban identity within the broader American context and, in turn, within a universal framework; by its sense of originality and identity; and by the link between knowledge and practice, expressed in the concept of utility. The true is the good, and the good is the useful – the means by which social and political transformation can be achieved.

In closing, we turn to historian Dr. Eduardo Torres Cuevas, who offers this final insight: «The lasting legacy of Félix Varela is not only that he initiated the path to ideological and political independence, but also that he provided a solid ethical foundation for the aspirations of the Cuban people. His vision placed truth not in the hands of the economic and intellectual elite, but in the hands of what he called «the rustic»-the common people. At a time when the oligarchy and its supporters avoided terms like «the people» and «the masses,» Varela boldly asserted that the people were the true agents of social change.

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez

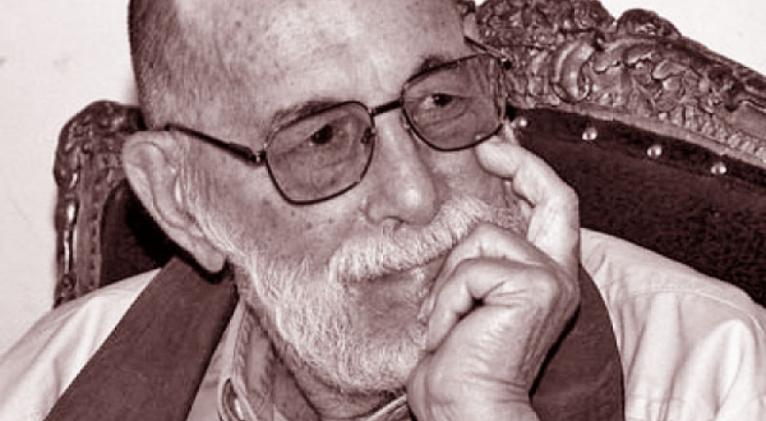

Photo: Tribuna de La Habana