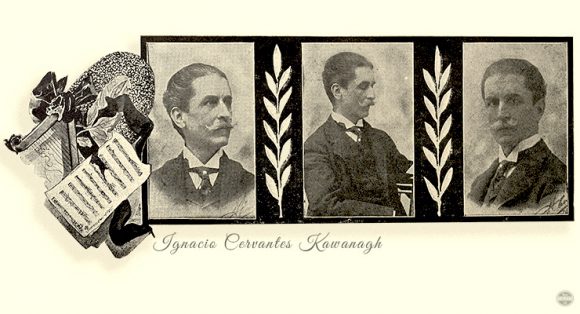

Ignacio Cervantes and His Devotion to Cuba

Ignacio Cervantes Kawanagh was born on July 31, 1847. His career, driven by natural talent and shaped through rigorous training, established him as one of the most distinguished composers of 19th-century Cuba and a revered music educator. Cervantes began his musical studies with his father and later studied with pianist Juan Miguel Joval, as well as composers Nicolás Ruiz Espadero and Louis Moreau Gottschalk. From 1866 to 1870, he attended the Imperial Conservatory of Paris under the guidance of Charles-Valentin Alkan and Antoine François Marmontel.

In his first year at the conservatory, Cervantes won its highest piano honor. Two years later, in 1868, he earned the First Prize in Harmony. During his time in Europe, he gained significant acclaim through concerts, public performances, and collaborations with renowned musicians and vocalists. His prodigious talent garnered praise from figures such as Gioacchino Rossini, Franz Liszt, and Charles Gounod.

Upon returning to Cuba in 1870, Cervantes was warmly welcomed by his peers. He gave numerous concerts and devoted himself to teaching. However, in 1875, he was expelled—along with violinist José White—for raising funds during performances to support Cuba’s independence struggle. Cervantes continued his activism in exile in the United States and Mexico. He returned to the island in 1879 and resumed both performance and pedagogy. From this period emerged his celebrated Danzas Cubanas for piano—works that embody the nationalist spirit prevalent in his music. His broader output included symphonic and chamber works, compositions for voice and piano, and zarzuelas.

Musicologist Orlando Martínez noted: “The Cuban dance for piano attains its own distinct and immutable status, and the term ‘contradanza’ disappears from our piano literature. (…) Cervantes’s Danzas Cubanas belong to the national heritage and reaffirm our identity—especially when life’s uncertainties or cultural shifts threaten our national dignity.”

Cervantes’s sense of Cuban identity was not a stylized construct; it emerged naturally in his work as a reflection of his environment and an act of artistic consciousness. His music blended nationalist sentiment with cultural nuance, helping define a sense of belonging that resonated across both the insurgent battlefields of Cuban independence and the island’s musical evolution.

Far from the detached refinement of European convention, Cervantes’s style—praised by critics and scholars—fused Romanticism with classical form. His performances were often described as elegant, expressive, and full of vitality. As Revista Cubana reported: “Cervantes is not a bland or cold pianist who plays notes like someone knitting. He is not an uninspired performer whose monotony lulls the listener to sleep. No—he is a fiery pianist who speaks eloquently through his instrument, who excites, captivates, and electrifies.”

For Alejo Carpentier, Cervantes worked from an original, inner vision. In Music in Cuba, the Cuban author noted that the composer understood national identity as something that could only be expressed through the musician’s individual sensitivity: “His Cubanness was internal. It was not a stylized version of something inherited (…) He was, therefore, one of the first musicians in the Americas to understand nationalism as the product of idiosyncrasy. (…) This makes him an extraordinary pioneer.”

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez

Photo: Cubadebate