José Dolores White Laffite: The Cuban Paganini

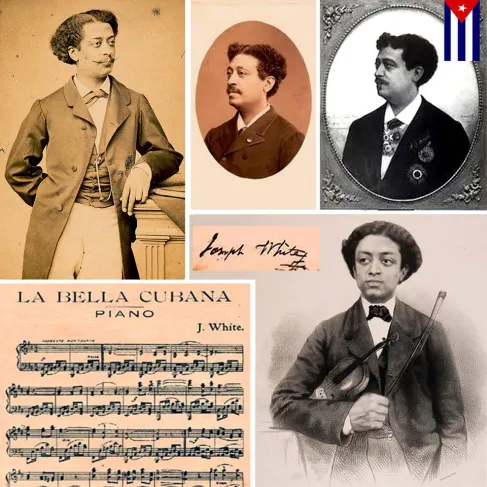

The world of nineteenth‑century music, dominated by European composers and performers, was shaken by the genius of a young mixed‑race virtuoso from Matanzas. José Silvestre de los Dolores White Laffite (1836–1918) broke through the barriers of racism and colonialism to become not only an internationally acclaimed violinist, but also a foundational pillar of Cuban musical identity.

His life reads as a story of prodigious talent, resounding success on the most demanding stages of Europe and the Americas, and an unwavering commitment to his roots. In a century when opportunities for artists of African descent were severely limited, White Laffite carved out a place in history and left behind a body of work that still pulses with the rhythms of the island.

He was born in Matanzas, the son of Carlos White, a French merchant and amateur violinist, and María Escolástica, an Afro‑Cuban woman and former enslaved person. He displayed an astonishing affinity for the instrument before the age of five and received his first lessons from his father. His precocious talent soon required more specialized teachers.

His early musical training in Cuba, however, was marked by the violence of the colonial regime. One of his first teachers, the Black violinist José Miguel Román, was executed in 1844 during the repression known as the Conspiracy of La Escalera. Despite this trauma, White continued his studies with the Belgian master Pedro Lecerf (also referred to as Haserf).

By the age of nineteen, he had already mastered sixteen instruments, including viola, cello, double bass, piano, guitar, and several wind instruments. His professional career took off in March 1854 with a concert at the Teatro Principal of Matanzas, where he was accompanied by the celebrated American pianist Louis Moreau Gottschalk. Impressed by his virtuosity, Gottschalk proved decisive for the young musician’s future: he organized a benefit concert to raise funds and encouraged White to pursue advanced studies in Europe.

In 1855, White arrived in Paris and enrolled at the prestigious Conservatoire, where he studied with the renowned violinist Jean‑Delphin Alard. His rise was meteoric. In July 1856, after only one year of study, he won first prize in the Conservatoire’s competition.

The jury’s verdict was unanimous, but the story behind it is revealing. According to a contemporary chronicle published in La Gazette Musicale, White was the last of twenty contestants to perform. The jury, exhausted from hearing the same concerto repeatedly, was transfixed when the young Cuban took the stage: “Mr. White appears as the final competitor… He, too, approaches the oft‑repeated concerto, which from that instant becomes a new work.” Parisian critics asked in amazement: “How has this son of virgin America become the equal of the greatest violinists known in Europe?” In the world capital of music, José White had not merely won a competition; he had announced the arrival of a genius.

White’s fame rested on impeccable technique and an interpretive depth that went far beyond sheer virtuosity. Critics of his time emphasized his absolute command of the instrument, refined technique, sober and elegant style, mastery of double stops, and remarkable rapport with audiences. His repertoire was vast and eclectic, intelligently adapted to the diverse publics he encountered on his global tours. In Cuba, he performed fantasies on operatic themes—such as Nabucco or Il trovatore by Verdi—and, crucially, works of national character.

Among the latter, his Popurrí de aires cubanos stood out—a piece that, according to contemporary accounts, made “the soul of the beloved land palpitate” and was often demanded as an encore. In Europe, he showcased works by Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, and the great Romantics, as well as pieces of extreme difficulty such as the Variations on the Carnival of Venice.

The impressions he made were recorded by leading musical publications throughout Europe and the Americas. In 1872, critic Victor Cochinat described him not merely as a performer, but as “a thinker… one of those bearers of the lyre, a contemporary Orpheus.”

Perhaps the most profound and moving appraisal, however, came from his compatriot José Martí, who heard him perform in Mexico in 1875. In three articles for Revista Universal, Martí devoted immortal words to White’s art. For the Cuban thinker, the violinist’s music was a transcendent experience: “all sorrow is forgotten, all pain eased, all love dreamed.” Martí captured the essence of his genius. Describing his interpretation of the Carnival of Venice, he wrote that the notes “no longer moan or slide—they splash, leap, burst forth: there they bind will and admiration.” He concluded with a statement honoring their shared origin: “In him I honor vigorous inspiration, and the tenderness and richness of my most beloved Cuban land. He owes his genius to the soul, and the soul to the fire that ignited and warmed it.”

Among his catalogue of more than thirty compositions—including a Violin Concerto in F minor, a String Quartet, and numerous salon pieces—one work has emerged as an enduring symbol: La bella cubana. Originally composed for two violins and piano, this habanera is regarded by musicologists as the most beautiful habanera ever written and one of the three most emblematic songs of Cuban identity. In it, White crystallized a synthesis of European academic training with Cuban rhythms, melodic turns, and sensibility. This was not superficial exoticism, but an organic integration that demonstrated how elements of island culture could flourish within the highest musical forms.

White’s career was profoundly itinerant, a succession of triumphant tours that established him as a global figure. After his early successes in Paris, he returned to Cuba between 1858 and 1860. He then lived in Paris from 1861 to 1874, where he became a member of the Conservatoire Concert Society and co‑founded several chamber ensembles.

A tour of the United States in 1875 led him to become the first soloist of African descent to perform with the New York Philharmonic, which accompanied him in March 1876. The American press praised him without reservation: “His style is perfection itself… his performance surpasses that of Ole Bull; he possesses more sentiment than Wieniawski.”

His political commitment, however, cut short his continued presence in his homeland. During his final stay in Cuba in 1875, he gave concerts with pianist Ignacio Cervantes to raise funds for the Liberation Army. Discovered by the Spanish colonial authorities, both musicians were forced to leave the island and went into exile.

This exile tour was monumental, taking him through Mexico, Panama, Venezuela, Peru, Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay. In 1877 he finally arrived in Brazil, where he experienced one of the most fruitful periods of his life. In Rio de Janeiro, White was appointed director of the Imperial Conservatory and served as a court musician to Emperor Pedro II. There he founded the Society of Classical Concerts, disciplined orchestras, and left a deep pedagogical imprint. He remained for fifteen years, until the emperor’s abdication in 1889, at which point he returned to Paris.

In Paris, White spent his final years as a respected professor and competition juror at the Conservatoire. Among his students were figures of the stature of French violinist Jacques Thibaud and, most notably, the Romanian genius George Enescu—an educational legacy that extends his influence across generations.

He died on March 15, 1918, in the very city that had consecrated him as a world‑class star decades earlier.

José White Laffite was not merely a technical phenomenon; he was a sonic bridge between Cuba and the world—a man whose violin sang with its own accent on the most demanding stages and who left behind a trail of sonic pearls that, like his immortal habanera, continue to resonate with the tenderness and fire of his homeland.

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez

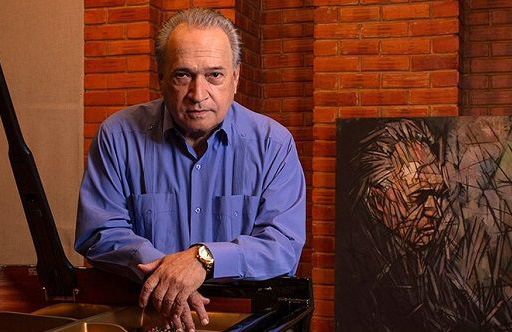

Photo: Cuba en la memoria