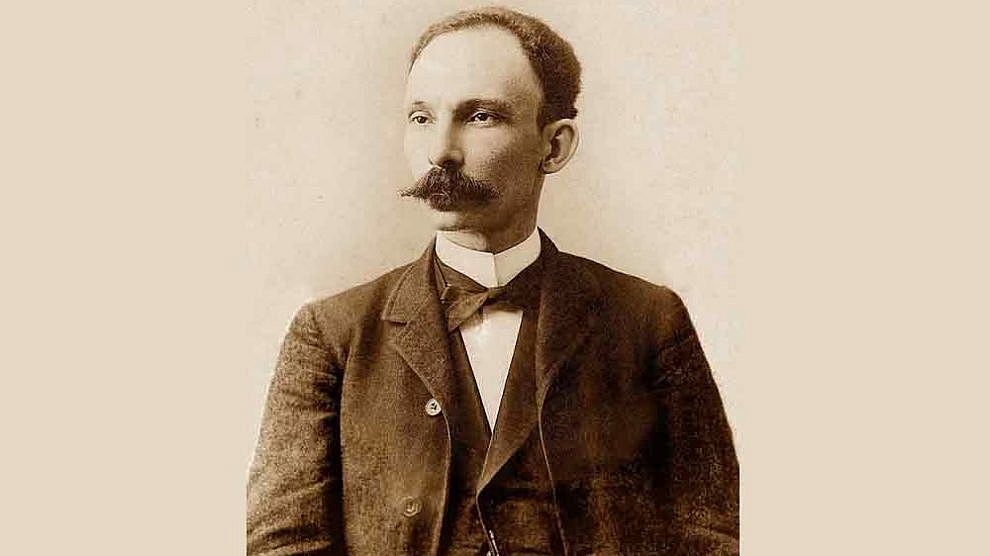

José Martí in Venezuela

“They say that one day a traveler arrived in Caracas at dusk, and without shaking the dust from his journey, he did not ask where to eat or sleep, but how to get to where Bolívar’s statue was. And they say that the traveler, alone with the tall, fragrant trees in the square, cried in front of the statue, which seemed to move, like a father when his son approaches him.”

This is how José Martí described his arrival in Venezuela on January 21, 1881, in a text titled Tres héroes, published in the first issue of the magazine La Edad de Oro.

The Apostle of Cuban Independence, in his journey through foreign countries after his stay in his homeland became impossible, spent time in the nation of the Orinoco and Maracaibo. There, his presence was significant both ideologically and in building a bond between Cuba’s independence struggles and those of other Latin American nations.

One of the most interesting facets of Martí’s presence in Venezuela is his vision of the country’s politics and social realities. In his writings, he expressed admiration for figures of Venezuelan independence, such as Simón Bolívar, and regarded Venezuela as a benchmark in the fight for Latin America’s emancipation.

Additionally, he became closely acquainted with its geography, culture, and people, and was able to collaborate extensively with Venezuelan press outlets such as La Opinión Nacional and the Revista Venezolana, which he himself founded, although it had a brief existence, publishing only its first issue.

His writings and speeches continued to reflect the bond he felt with the land of Bolívar. In several of his texts, he defended the cause of Venezuelan freedom and, through his contacts with various leaders, reinforced the idea that the struggle for Cuba’s independence and Latin American unity should be a collective effort, not the responsibility of a single country.

Ultimately, the Master considered himself a son of all Latin America, perceiving the continent as one single, great nation.

His stay in Venezuela was not very long. His libertarian ideals and firm principles came to irritate then-president Antonio Guzmán Blanco, who, on July 27, directly ordered, through his aide-de-camp, that Martí leave the country. Thus, aboard the steamer Claudius, he arrived in New York on August 10, 1881, where he fully dedicated himself to preparing the final stage of the War of Independence.

The love of the Apostle for the land of the Liberator is evident, as revealed in his writings and correspondence. In a letter to Fausto Teodoro de Aldrey, owner of La Opinión Nacional, on the day he received the president’s order to leave the country, Martí wrote: “I have felt very noble hearts beating in this land; I repay its affections passionately; its joys will be my delight; its hopes, my pleasure; its sorrows, my anguish,” and later: “Give me something to serve Venezuela with: she has in me a son.”

In this farewell letter, Martí made it clear that he harbored no resentment toward the nation he defined as the cradle of Latin American independence: “[…] for sweet lips, there is no bitter cup; nor does the asp bite valiant hearts; nor do faithful children renounce their cradle.”

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez