Martí’s Image Against Time

Perhaps it is inscribed in the hazy appearance of memory—the power of images over recollection—like an innate quality that transports us to bygone times, encapsulated in a visual and narrative form that allows us to relive the past. Within this context, the iconography of José Martí, deeply rooted in the significance and depth of his figure as both a national and universal hero, has drawn the attention of scholars who have recognized the consistency and value of photography. Even within its own artistic framework, photography is capable of complementing and enriching the world portrayed in the works of the Apostle.

Whether as a representation, as an inspiring symbol of a broader vision of Cuba and its essence, or as the undisputed guide toward the highest ideals we can aspire to, the images in Martí’s iconography derive their singular power from his gaze. It is in his eyes that contemplation gives rise to thought—captivating both his contemporaries and those who came after him.

Allegorical paintings and related works reinforce this influence, serving as a measured yet definitive testimony to both Martí’s stature and his closeness, without diminishing the visual impact of the images in which he appears. As researchers Ottmar Ette and Titus Heydenreich observe, in alignment with Martí’s patriotic-revolutionary project: “If modernity, for him, was the transient and the ephemeral, the image he wished to project for posterity was that of a simple man—one who stood beyond fleeting trends and the circumstances that distanced him from his homeland.”

Thus, they assert, Martí’s image is—simple, yet not merely modest—the image of a man, an original creation in which the subject and object of artistic expression become one.

This dynamic has captivated numerous scholars and artists over the years. As poet, essayist, and art historian Jorge R. Bermúdez notes, Martí’s presence as one of the most prominent themes in Cuban art has remained a constant throughout his years of study: “Martí has been so frequently and masterfully painted, sculpted, engraved, and photographed over more than a century that one could trace the evolution of Cuban art simply by examining the body of work centered on him.”

Indeed, he emphasizes, the major trends and movements in modern art history are reflected in these depictions, with varying degrees of success among the artists who have taken up the subject.

«From an aesthetic and communicative perspective, it is essential to highlight the referential power of Martí’s photographic iconography. Almost all of our most important visual artists have their own interpretation of José Martí. It was through his deep understanding of photography—humanity’s first technical image and a new means of democratizing art, knowledge, and communication—that Martí grasped the significance of having his portrait taken. He understood the lasting impact that these photographs, tangible records of his immense efforts, would have on our most representative artists. It is no coincidence that his dedications and portraits took on a truly literary dimension, spanning from the verses accompanying his youthful photographs to full-fledged prose poems in the portraits of his intellectual maturity,” Bermúdez explains.

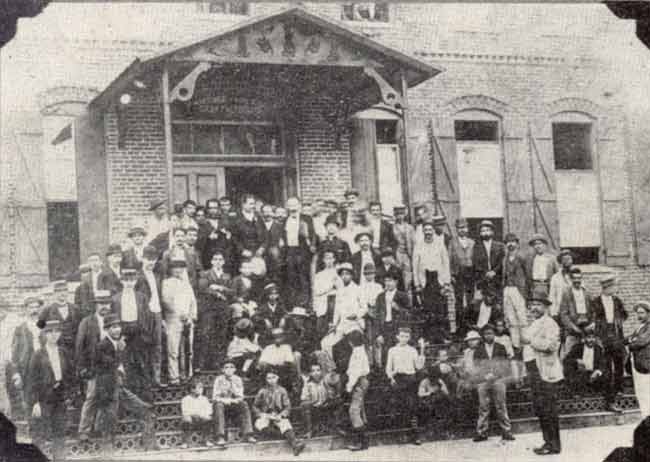

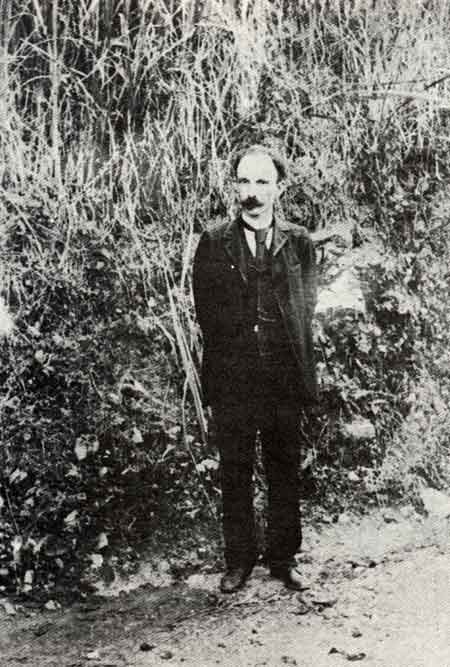

Images such as the one from his imprisonment, the photograph with Cuban exiles in Key West, the portrait with his son José Francisco, and the full-length image taken in Jamaica exemplify the enduring power of Martí’s visual legacy. They continue to inspire excellence and creativity, reflecting both the vastness of his vision and the brevity of his existence—an existence that made him, unequivocally, the most universal of all Cubans.

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez