René Portocarrero and the Universality of Cuban Painting

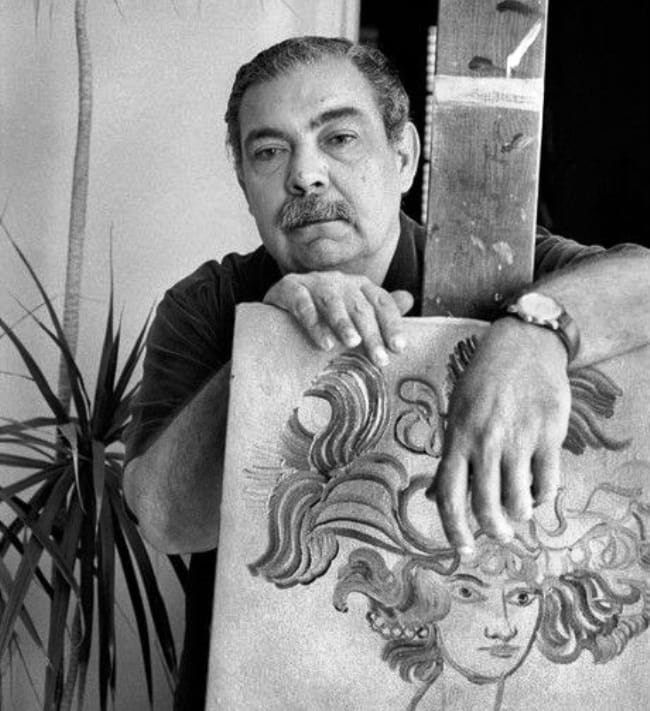

When René Portocarrero passed away on April 7, 1985, he had already established himself as one of the foremost figures in Cuban painting. Among the many accolades he received were the Félix Varela Order, Mexico’s highest honor, the Águila Azteca, and his appointment as an honorary member of the International Association of Visual Artists at UNESCO. The Baroque elements present in his artwork always retained a local interpretation, drawing from a nearby, personal heritage. In his compositions, Portocarrero elevated these elements into a kind of visual poetry, born of his self-taught training and the expressive conditions he explored.

In La cantidad hechizada, José Lezama Lima acknowledged the painter’s affinity for the spaces and corners of his hometown, Havana, which also influenced many of his other works. Lezama Lima wrote:

«In his labyrinths of figures, Portocarrero prepared a diverse collection for his plazas. For this, he needed the medieval order of the city, where one engages in growth through craft, through the ceremonial acts of war or religion, through the games of arms. The plaza was the sanctuary for those immense parades, whether they were the procession of merchants or the depiction of sacramental plays, masquerades and minstrels, the brilliant colors of the budding seasons and the dark frenzy of death dances. Portocarrero used the plaza as a magical quartz, enabling him to see the boundaries of each object in its unity, and the interweaving of diversity.» He further detailed:

«Portocarrero painted the Plaza de la Catedral during a festival. Graceful couples of joyous Creoles indulge in the undulating rhythms of one of our contradanzas. The entire foreground is filled with a tumultuous crowd, which the dance gives form, proportion, and gentle frenzy. The cathedral in the background is not yet depicted in its Gothic ascension but through the curvilinear development of a Baroque portal. The undulations of the dance seem to rest on the curved Baroque forms, which embrace the spaciousness and diversity of the horizontal. In the curvature of the stones in the portal and of the bodies in the dance, the breeze, purified by the hills and beaches, extends a voluptuous hue of blues, speckled gold, and coral stripes.»

Portocarrero began his career as an educator at the Estudio Libre de Pintura y Escultura in 1937. His drawings were published in magazines such as Orígenes, Verbum, and Espuela de Plata. He also taught drawing at the Havana Prison in 1942, where he created a religious mural and two oil paintings for the Church of Bauta.

In 1944, Portocarrero created a series on rural landscapes and exhibited his work at the Museum of Art in New York. Two years later, he produced a series of pastels focusing on popular festivities. At that time, he decorated ceramic pieces at the Santiago de las Vegas workshop and recreated the mural Historia de las Antillas at the Habana Hilton. Other murals were later created in similar institutions, such as the National Hospital and the National Theatre of Cuba.

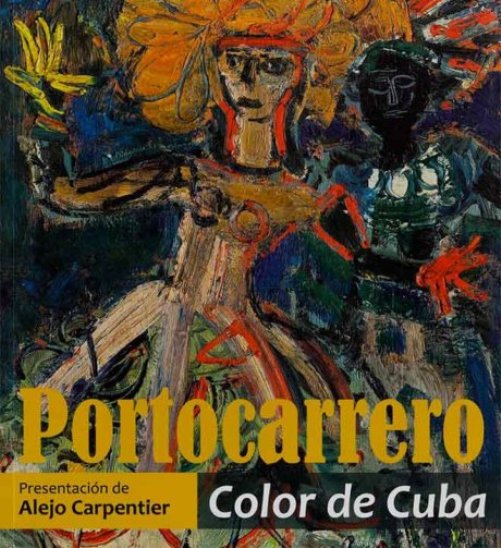

One of his later series was connected to floral themes and ornamented women, both of which were featured in his acclaimed works at the 33rd Venice Biennale. Color de Cuba, one of his most renowned exhibitions, integrates religious images tied to Cuban Santería, carnival figures, and ornamental women. He further explored these themes in exhibitions like Carnavales. In the catalog notes for this exhibition, Alejo Carpentier wrote:

«Portocarrero has gone, with a steady hand, to the root of things, understanding that before what is reflected or illuminated, there were elements of a Baroque style in perpetual motion, so present in the colonial architecture with its deep courtyards, in the orange light of a twilight, as in the living and tireless world. But for him, it was not about representation; it was about transcription.»

In an interview with journalist and researcher Mercedes Santos Moray, Portocarrero explained:

«There have perhaps been manifestations of every aesthetic nuance, from the primitive to the abstract, from realism to hyperrealism. But there has always been a desire, a peculiar intention to create objectively revolutionary painting… I would say that my painting before the Revolution had a drama that has since been washed away. We tend toward a Cuban art of universal projection. I believe that everything that is native, expressive, and authentic, with those virtues, is what produces true universalism.»

According to several critics, Portocarrero’s views on art were rooted in the balance of forms and colorography—both of which were key features in the chaotic environments present in much of his work. Despite this, he never abandoned the harmonious conjunction of elements, the composition of shapes, and the layering of colors in each narrative scene and in the exploration of themes.

With a lasting legacy in the history of 20th-century Cuban art, Portocarrero infused his figurative works with a Baroque style at its core. Within this style, the common and unique elements of his artistic expression remain timeless, transcending the passage of time and enriching the art world he contributed to throughout his life.

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez