Rubén Martínez Villena: Poetry and the Wakeful Eye of the 1930 Revolution

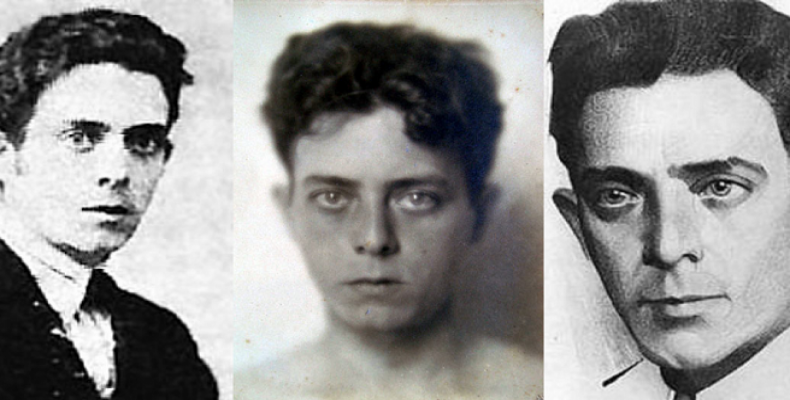

A boy with a penetrating gaze that impressed General Máximo Gómez grew into the poet who laid down his pen only to help shape the destiny of a nation through both strikes and sonnets.

For new generations of Cubans, the name Rubén Martínez Villena may seem like yet another historical figure from the early 20th century. Yet his life, condensed into only 34 years, was a rare convergence of acute lyrical sensitivity and resolute revolutionary action. He was the intellectual who, after winning poetry prizes, led the first national political strike; the lawyer who defended Julio Antonio Mella and immortalized Gerardo Machado as a horned donkey.

On the anniversary of his death, January 16, 1934, we remember not only a combatant but a builder of consciousness, a poet who found in the struggle for social justice the purest expression of his art.

Born in Alquízar in 1899, Villena grew up in an educated middle-class family that, after returning from exile, lived the frustration left by U.S. intervention in the War of Independence. His literary talent was precocious: at eleven, he wrote his first verses, and by twenty-one, he was a recognized poet in Havana magazines. To please his mother, he completed his law studies with distinction in 1922.

Yet Villena’s destiny was never conventional. Working at anthropologist Fernando Ortiz’s law office connected him with young, critical intellectuals and exposed him to progressive ideas. The young poet soon realized that his true vocation went beyond verse—it demanded transforming the reality of a republic weighed down by corruption and subservience.

On March 18, 1923, at the Havana Academy of Sciences, during a tribute, a group of fifteen young men led by Villena rose to denounce a scandalous act of corruption by President Alfredo Zayas: the fraudulent sale of the Convent of Santa Clara. This act, known as the Protest of the Thirteen, was more than a mere complaint. Intellectuals like Juan Marinello saw it as the start of the “critical decade,” a period of intense political mobilization and radicalization. Researcher Fernando Martínez Heredia described that outcry as Cuba’s overture to 20th-century modernity. Among the thirteen signatories of Villena’s manifesto emerged key figures of Cuban intellectual and political life, including Marinello, Jorge Mañach, and José Zacarías Tallet.

From that moment, Villena assumed a natural leadership role. He co-founded the Falange de Acción Cubana, advocating national renewal through public education, free from partisan interests. In 1927, he also signed the Grupo Minorista Declaration, calling for new art, university reform, economic independence, and resistance to U.S. imperialism.

Villena’s political maturity led him to join Cuba’s first Communist Party in 1927, becoming one of its core leaders. From there, he tirelessly organized workers, serving as legal advisor to the Confederación Nacional Obrera de Cuba and confronting Gerardo Machado’s dictatorship, which had taken power in 1925.

Paradoxically, as his combative spirit strengthened, his body weakened. In 1927, he was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis, a disease that accompanied him until his death. Yet his activity never waned.

In 1930, as a member of the party’s Central Committee, he organized and led Cuba’s first political strike, which paralyzed the nation for over 24 hours. Persecuted, he traveled to the Soviet Union, hoping to both escape Machado’s terror and recover his health. There, he worked with the Komintern, but doctors gave him an irreversible prognosis.

He returned to Cuba, driven by the desire to see his newborn daughter, Rusela, and devote his remaining strength to the struggle. From clandestinity, despite failing health, his strategic mind remained active. He was the principal organizer and leader of the revolutionary general strike that, on August 12, 1933, overthrew Gerardo Machado.

Villena’s poetry was neither vast nor abundant, but intense and revealing. His friend, writer Raúl Roa, noted that although Villena lived for verse, his work was scarce, yet he considered him the most distinguished and authentically personal poet of his circle.

His poetry evolved from romantic and erotic intimism—as in the sonnets “Declaración” and “El rizo rebelde”—to lyricism committed to the epic episodes of Cuba’s independence struggles, such as “Máximo Gómez” and “El rescate de Sanguily.” Critics like Cintio Vitier note ironic sentimentality, a languid and morbid pessimism mingled with the inflection and fire of José Martí’s Versos libres.

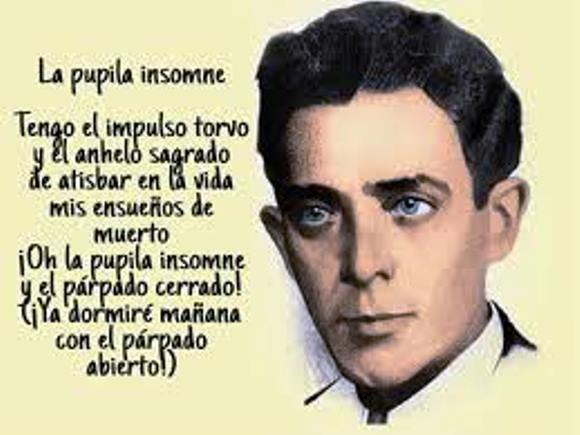

No poem better illustrates his attitude toward life and his genius than “Canción del sainete póstumo,” written in 1922. With caustic, desacralizing humor, it anticipates his own death and wake, describing with detachment the hypocrisy and bourgeois ceremonial surrounding him. Lines such as “Yo moriré prosaicamente, de cualquier cosa / (¿el estómago, el hígado, la garganta, ¡el pulmón!)” chillingly foreshadowed his death from tuberculosis.

This poem, seen as part of the dawn of the literary avant-garde, symbolizes Villena’s shift toward a worldview marked by irony and disillusionment with the republican reality, which only revolutionary action could redeem. For him, as for José Martí, whom he admired, true poetry resided in social transformations creating a fairer world.

Rubén Martínez Villena died at La Esperanza sanatorium, on the outskirts of Havana, on January 16, 1934. His death coincided with the closing of the Fourth Congress of Trade Union Unity. Worker delegates, bearing their credentials and banners, led his funeral procession, followed by over twenty thousand workers paying tribute with revolutionary slogans.

His legacy is dual and inseparable: the organic intellectual who dedicated his pen and thought to the struggle, and the revolutionary strategist who mobilized the masses even from illness and clandestinity. He demonstrated that culture and politics are not separate realms but facets of the same fight for national dignity.

In one of his most famous poems, he wrote a line that became both a slogan and a definition of his existence: “Hace falta una carga para matar bribones, / para acabar la obra de las revoluciones….” Rubén Martínez Villena himself embodied the vital charge of intelligence, courage, and poetry that Cuba of the First Republic needed. His wakeful, critical eye still watches us from the depths of history, reminding us that true literature not only describes the world but strives to change it.

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez