Zenea, Romanticism, and the Reign of Reality

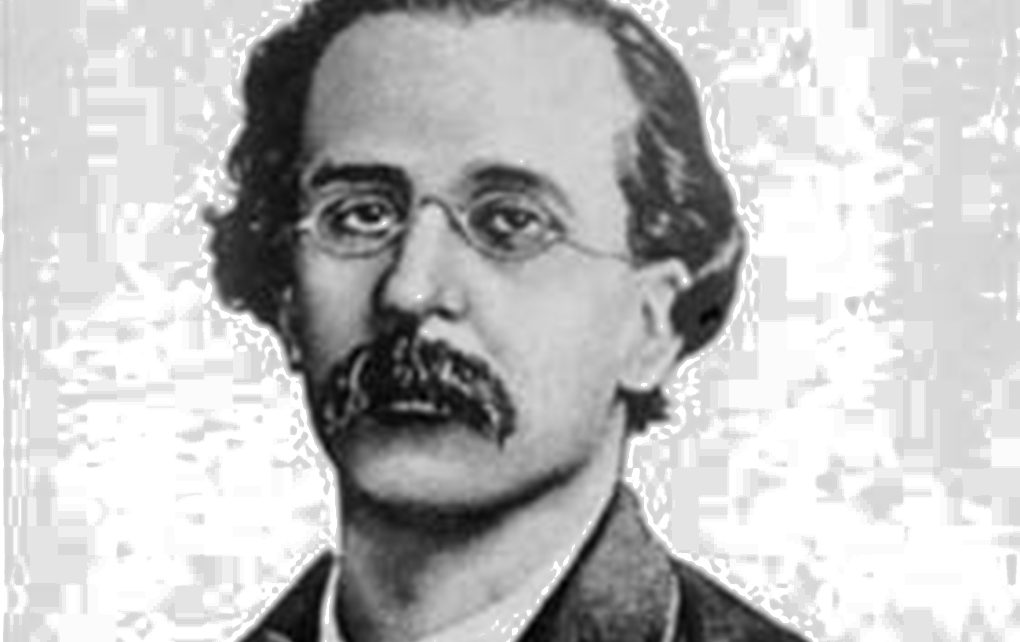

On this day, in 1832, Juan Clemente Zenea y Fornaris was born in the city of Bayamo. He was the son of a Spanish lieutenant and the sister of the poet José Fornaris. Zenea became a poet deeply rooted in the Romantic movement that flourished in Cuba.

As Lezama noted in his Introduction to Zenea: «(…) he is the first Cuban poet with a true poetic culture, that is, a culture born from poetry itself—from the subtle progressions of metaphor, from the connections between body and image. (…) He is a revitalizer, a clarifier, a shaper of our poetry.»

In 1845, Zenea enrolled at El Salvador College in Havana, and just a year later, he published his first poems in La Prensa. At this institution, José de la Luz y Caballero taught classes, though many biographies emphasize that Zenea acquired much of his knowledge through self-dedication. During this time, he contributed to La Voz del Pueblo and co-edited El Almendares alongside Idelfonso Estrada.

In 1852, Zenea traveled to New Orleans, where he met his great love, actress Adah Menken. He collaborated with several publications and joined the Orden de la Joven Cuba. Later, he moved to New York, became a member of the La Estrella Solitaria society, and wrote for La Verdad, El Filibustero, and El Cubano, expressing his support for the annexationist movement. Under Spanish colonial rule, violence was a common response to Cubans, regardless of whether they openly opposed the crown.

The following year, Zenea was sentenced to death, but thanks to a general amnesty, he was able to return to Cuba, where he remained for over a decade. During this time, he founded and directed Revista Habanera and contributed to numerous publications, including Guirnalda Cubana, La Piragua, Brisas de Cuba, Floresta Cubana, Revista de La Habana, El Regañón, Álbum cubano de lo bueno y de lo bello, La Chamarreta, El Siglo, Ofrenda al Bazar, and Revista del Pueblo. He also collaborated with Spanish publications such as La Ilustración Republicana Federal and La América. Additionally, he co-founded and edited the newspaper La Revolución alongside Néstor Ponce de León and contributed to El Mundo Nuevo and América Ilustrada.

When the Ten Years’ War broke out in 1868, Zenea was in the United States and took part in the ill-fated Catherine Whiting and Lillian expeditions. In 1870, he secretly entered Cuba. After meeting with Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, he attempted to return to the United States but was captured by a Spanish volunteer column. He was held for eight months at La Cabaña fortress before being executed on August 25, 1871. «Zenea himself became a victim because he trusted the guarantees given by the Spanish diplomat in New York.

Once imprisoned, he realized that his death had been predetermined. The delay in carrying out his execution was part of the pleasure of cruelty,» explained renowned researcher Ana Cairo. Assessments of Zenea’s legacy were influenced by divisions within the Cuban exile community, which was split between Aldama and Quesada supporters, as well as by the failed expeditions and the perception of his role in them.

These factors led some contemporaries to question his loyalty. On this, poet and essayist Cintio Vitier remarked: «Could a poet of such pure and restless soul, marked by impeccable conduct and unwavering revolutionary commitment, have been a traitor in disguise? We never believed it, above all, for poetic reasons. Morality can be feigned or broken; courage is not exclusive to heroes, nor even to honest individuals. But the transparency of poetic expression is always infallible, even ruthless.»

Zenea wrote his last verses during the eight months he spent in solitary confinement in a dungeon at La Cabaña, facing the certainty of death. These verses—published posthumously by Piñeyro under the title Diario de un mártir—reveal the absolute clarity of his conscience. Those who see poetry as mere ornamentation, those incapable of discerning its authenticity, may find this argument inadmissible.

However, it was precisely this argument that José Martí put forth when, on December 8, 1894, in Patria, recalling the poet’s ‘days of death,’ he evoked those «verses of august serenity, where there is not a single note of confusion or remorse from a man who understands souls.» (…) After so much suffering, he could finally rest in peace—because he had lived and died at peace with his conscience, as a brave man, as the last of the great Cuban Romantic poets, embodying its deepest and most enduring essence.

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez

Photo: Cubaperiodistas