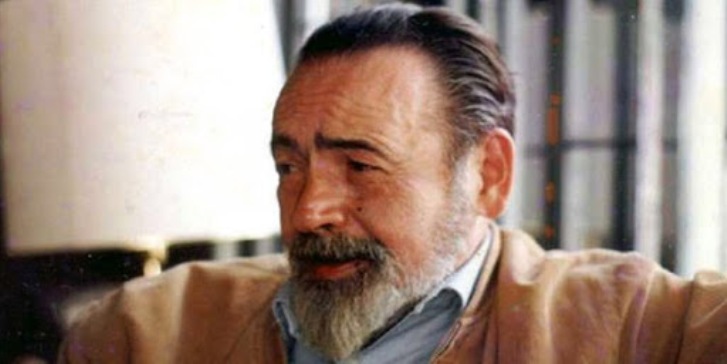

Eliseo Diego and the Faith of Creation

Unique and vital in its essence, and diverse and plural in its manifestations, good art not only contributes to seeing the world with different eyes but also to reflecting on an act of self-awareness, whether overt or discreet, but subjugated by the demands of a spirit and its response to reality.

For Eliseo Diego, that passion was represented in his poetry, although he also demonstrated excellent skills as an essayist and had an early foray into narration. His poems, grounded in the rediscovery of the potential of the human being, transitioned from popular aspects to broader ones, which, despite their universality, did not lack development and depth in the lyricism of their expression.

From «En la calzada de Jesús del Monte» (1949) to works like «El oscuro esplendor» (1966), «A través de mi espejo» (1981), or «Inventario de asombros» (1982), Diego equipped himself with a clear expression to give direction to writing as a vehicle for expression. «And I do it not out of vanity or the desire to shine, or what do I know, but out of necessity because I have no choice but to write these things called poems,» he expressed at some point. He also compiled prose in works such as «Divertimentos» (1947), «Versiones» (1970), and «Noticias de la quimera» (1975).

The Orígenes Group had a significant impact on his formation. He was a founder of that collective, as well as the eponymous publication, alongside figures like José Lezama Lima, Gastón Baquero, Cintio Vitier, Finar García Marruz, Julián Orbón, and other intellectuals connected to that group committed to preserving the identity of the Cuban nation. «We had the feeling that the Cuban essence, part of this identity, of this idiosyncrasy, of this identity we call Cuba, was unraveling, and it’s an island,» he affirmed in an interview.

As an interpretation of possibilities, Diego appreciated considerations on reality after 1959: «(…) if within a material universe there is a way to organize human society, to find a more just and reasonable order for human society, the fact that you believe in God or not should not and cannot prevent you from supporting or adopting this way of organizing society.»

However, this stance was not clear-cut. In line with the contrasts of each era, his figure generated unclarified debates. The emergence of the weight of circumstances does not justify irrationality, especially when other models with inaccuracies and rhetorical embellishments devoid of any excuse or self-reflection persist silently. Therefore, remembering Eliseo Diego on this, the anniversary of his departure, is not trivial.

In this regard, Eliseo Diego’s son commented: «The poet Eliseo Diego was a generous patriarch who exercised an irresistible fascination; a true Habana resident, a conversationalist, and as charming as they come, Dad enchanted everyone with his way of telling stories of the island’s tragicomedy, until he fell asleep in the dining room chair without saying goodnight, with a glass of brandy resting on his thighs.»

His work is structured as a complete and autonomous universe, focused on the ability to grasp reality or time with words and evoke them after the loss of innocence and original fullness. This is why all his books are artifacts in both the etymological and literal senses, as affirmed by Ángel Esteban, who also values the unique conviction in his essays linked to the urgency of returning to the model and experience of childhood to achieve absolute maturity and expressive capacity. «Eliseo Diego’s essays maintain consistently similar theoretical proposals, revolving around the artist’s possibilities to express the deepest, the clearest, what comes closest to the thing itself. In some cases, the smallest ends up being the biggest.»

Aramís Quintero, one of the most prominent scholars of his work, expressed regarding this idea: «Each book is itself an artistic, poetic object, revealing the same artistic personality found in each poem, a love for detail and the whole that translates into completely finished pieces. In all of them, the same author is revealed, and they are closed citadels around his fundamental motivation.»

For Eliseo, poetry is fundamentally an essential experience for every human being and ultimately does not need to be expressed in words. «There are very simple people who, with their way of living, have already created a poem. When you encounter the way these people live, it seems like you are in front, so to speak, of the majesty of poetry. Some people write poetry, others live it. But another issue I have already raised is the problem of poetry as the need to communicate to someone this experience, to have the testimony that one has seen and felt the essential experience of poetry.»

In the compilation of «Nos quedan los dones,» it is affirmed that all his writing is endowed with a kind of macro and microcosmic structure, giving his opera omnia a closed and complete character marked by the constant obsession with reaching the essence of things, apprehending it with words, and evoking it afterward: «(…) even in his latest poems from the nineties, his work takes on an unmistakable personal tone, as well as a remarkable ability to control times and spaces and to poetically treat themes, circumstances, and places.»

The intrinsic need for poetry is evident in Eliseo’s work. The connection of that need with the spirituality of a man like him offers a picture that invites multiple readings. Let the words of the narrator and essayist Rafael Almanza serve as further motivation: «Readers of poetry were always few, and now they are fewer than ever. But anyone who lives for something more than just extending in time will eagerly approach Eliseo’s poetry for a quality of news and blessings as there are few in the current Spanish language. He shows us that the writer can trust in the faith lived from the depths, not as sentimental entertainment, a fashion, or a business, but for the deployment and strength of his personal expression. Faith does not limit; it makes us grow.»

Translated by Luis E. Amador Dominguez